Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is often misunderstood, especially its claim that the Federal Government finances itself through money creation. At money-central.com, we believe in providing clear, expert analysis of complex financial topics. Building on insights from MMT, this article breaks down this seemingly radical idea, using simple terms and T-accounts to illustrate how it works. Forget the myths about taxes and bonds being the sole source of government funds. We’ll explore the concept of “Always Money” in government finance and uncover the reality behind federal spending.

To understand this, we first need to clarify the structure of the U.S. government. It’s more than just the Treasury; it’s a consolidated entity including Congress, the President, the courts, and even the Federal Reserve in certain monetary analyses. Why is this constitutional and legal framework crucial? Because debates about MMT and government finance often get bogged down in misunderstandings about the Federal Reserve’s role. Many discussions miss the fundamental legal point: when analyzing the relationship between the government and the private sector, consolidating the Federal Reserve with the rest of the federal government is essential for clarity.

The Federal Reserve System, while seemingly independent, is integral to the Federal Government from an MMT perspective. The confusion often arises from the structure of Regional Federal Reserve Banks, which are congressionally created corporations. Conspiracy theories abound, suggesting the Federal Reserve is a private entity controlling the monetary system because member banks own “shares” in these regional banks.

However, these “shares” are not equity in the traditional sense. As the court case Wells Fargo v. United States clarified, functional ownership and control of the Federal Reserve Banks (FRBs) reside with the Treasury and the Federal Reserve Board. The net earnings of the FRBs are directed to the Treasury, and excess earnings are remitted there. The “capital contributions” from member banks function more like debt instruments, not equity. Therefore, money created by the Federal Reserve is fundamentally a product of the “public fisc,” just like money from the Treasury. Consolidating the Federal Reserve System with the broader Federal Government, similar to how government-owned corporations like the Post Office are consolidated, provides a more accurate picture for monetary analysis.

Understanding the Federal Reserve System's Place in Government

Understanding the Federal Reserve System's Place in Government

This legal foundation is key to understanding MMT’s core argument: the Federal Government always “money-finances” its spending. This doesn’t mean the Treasury can simply demand an overdraft from the Federal Reserve. Instead, MMT scholars argue that when we consider the entire Federal Government, including the Federal Reserve and Congress, budget deficits are inherently money-financed due to continuous coordination between the Treasury and the Federal Reserve. This coordination manifests in two critical ways:

- Liquidity Provision: The Federal Reserve constantly ensures liquidity in U.S. Treasury markets, directly or indirectly.

- Payment Clearing and Auction Support: Daily coordination between the Federal Reserve and the Treasury ensures smooth payment clearing and successful Treasury auctions.

The 2020 Coronavirus crisis highlighted this coordination, as the Federal Reserve launched massive Treasury security purchases to stabilize a malfunctioning market. As long as Congress authorizes Treasury securities, this system remains functional.

The debt ceiling introduces a potential complication – a legal limit on Treasury security issuance. However, MMT’s consolidated view of the Federal Government becomes crucial here. Congress’s power of the purse, the authority to spend and tax, is constitutionally paramount. Debt ceilings are statutory limits, secondary to Congress’s fundamental spending directives. Legal scholars like Michael Dorf and Neil Buchanan argue that in a debt ceiling crisis, the President should prioritize constitutional obligations, even if it means exceeding the debt ceiling. Rohan Grey expands on this, suggesting that money creation through mechanisms like a large denomination platinum coin is a less unconstitutional, even constitutional, option. The underlying principle is that congressionally mandated spending should not be halted by the debt ceiling. The government will find a way to fund its obligations, ensuring “always money” is available to keep functioning.

Ultimately, the intricate accounting details often distract from the larger constitutional reality. Congress holds the power of the “public fisc.” The Federal Reserve and Treasury are institutions created by Congress, delegated some of this money power. As Wells Fargo v United States affirmed, funds created by the Federal Reserve are public funds, originating from the same “fisc” as Treasury funds. The Treasury’s account is simply one manifestation of Congress’s broader power of the purse.

Now, let’s move to the monetary mechanics and examine the “always money” concept in practice. Initially, it seems logical that taxes and bonds finance government spending. The Treasury needs to maintain its account at the Federal Reserve. Seigniorage from coin production provides a small revenue stream. But this is minimal compared to budget deficits. Critics often dismiss MMT by pointing to the seemingly obvious need for taxes and bonds to fund government operations.

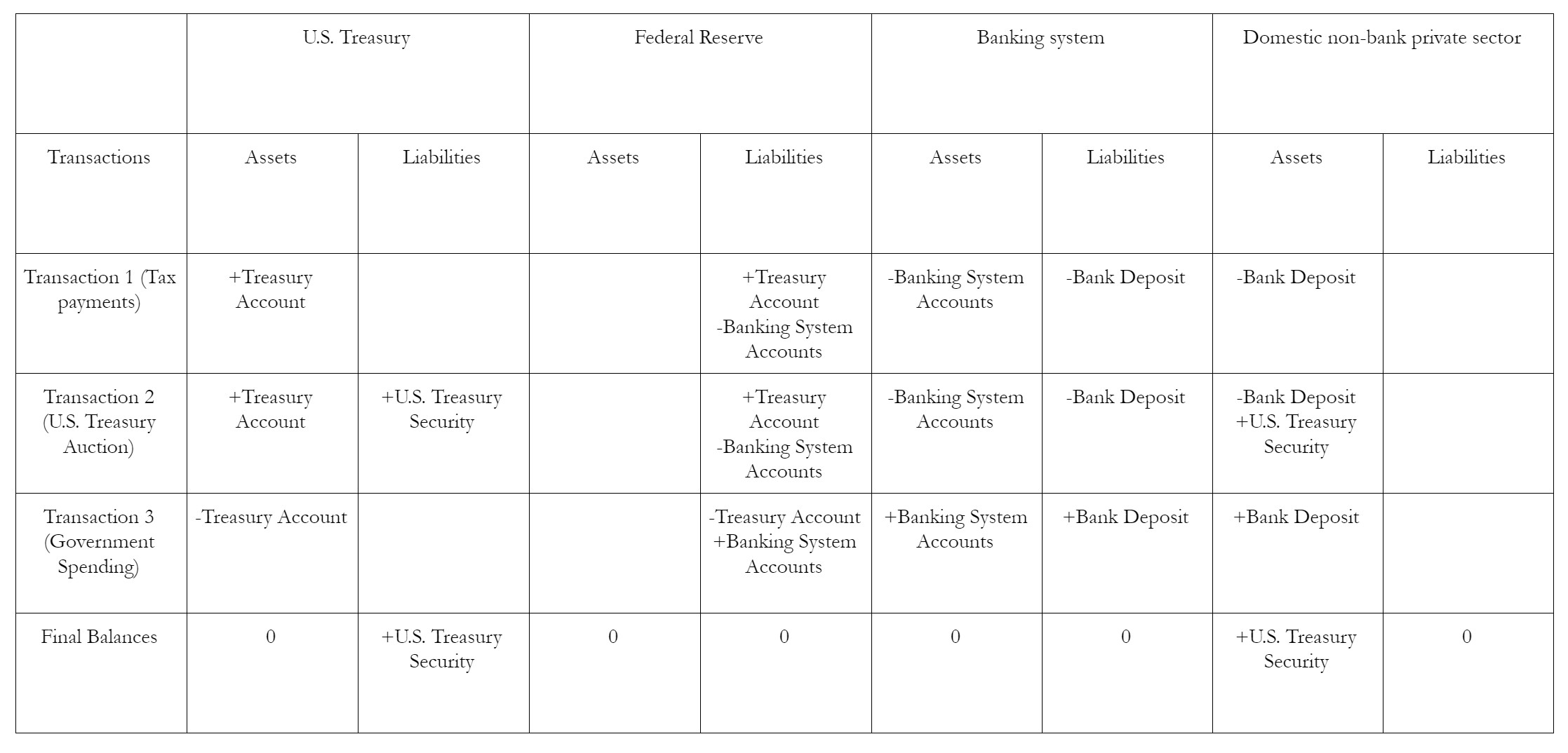

Let’s analyze this with macroeconomic accounting, using T-accounts to visualize the transactions.

However, this simplified view misses a crucial element: the need for settlement balances within the banking system. Taxes and Treasury auctions require sufficient reserves (settlement balances) in banks’ accounts at the Federal Reserve to clear. Historically, the Federal Reserve and Treasury coordinated daily to manage these balances, injecting and draining reserves as needed, often using repurchase agreements for temporary injections. For simplicity, consider outright purchases by the Federal Reserve. Let’s see how these transactions appear when we consolidate the entire Federal Government.

From this consolidated perspective, the “always money” concept of MMT becomes clearer. Government spending increases government liabilities and private sector assets. Treasury auctions merely shift the form of government obligation held by the private sector, without altering the total government liabilities outstanding. The Federal Reserve’s role in ensuring auction success by purchasing bonds further reinforces this. What appears as “financing” is essentially internal government accounting. Primary dealers act as intermediaries to ensure smooth Treasury auctions, but the underlying dynamic remains the same.

Imagine a simplified system where the Treasury sells securities directly to the Federal Reserve, which then sells them to the private sector after spending occurs.

The result is virtually identical. The government creates money, the private sector receives it, and securities are sold to manage liquidity. Another perspective is the proposal for the Treasury to finance spending directly through large denomination coin issuance and for the Federal Reserve to issue its own securities. This aims to simplify government financial operations and highlight the existing reliance on money-finance.

Under this proposed system, the consolidated transactions are remarkably similar. The core mechanism of government money creation and subsequent liquidity management through security sales remains consistent. The difference lies in the institution issuing the securities (Federal Reserve instead of Treasury). While legally significant – potentially resolving debt ceiling issues – it doesn’t fundamentally change MMT’s argument about “always money” and government finance. It simply clarifies that government securities are a monetary policy tool, not a primary financing tool for the Federal Government as a whole.

In Conclusion

Understanding MMT’s argument about “always money” requires careful consideration of legal and accounting details. It’s not about semantics; it’s a coherent and insightful analysis of how our monetary system actually functions. To reiterate the key propositions:

- Consolidating the Federal Reserve with the rest of the Federal Government is appropriate for analyzing fiscal and monetary policy.

- The Federal Reserve ensures continuous liquidity in Treasury markets.

- Daily coordination between the Federal Reserve and Treasury supports payment clearing and Treasury auctions.

- Therefore, the Federal Government finances spending through money creation, while Treasury auctions serve a monetary policy purpose, not a financing one for the consolidated government.

- This argument holds even without direct Treasury overdrafts or direct security sales to the Federal Reserve.

- In debt ceiling crises, money creation becomes a necessary option to uphold Congress’s power of the purse.

- A more efficient system might involve the Federal Reserve managing security auctions and the Treasury directly financing itself through money creation.

Whether you agree or disagree, this is the essence of MMT’s argument. Critiques should address the legal reasoning or the macroeconomic accounting. The “always money” concept, properly understood within the MMT framework, challenges conventional notions of government finance and offers a crucial lens for analyzing modern monetary operations. For a deeper dive into the legal foundations, explore Rohan Grey’s insightful law review article.