What This Guide is About

This guide is designed to empower you to write compelling grant proposals that secure research funding across all academic fields—from sciences and social sciences to humanities and arts. Primarily aimed at graduate students and faculty, the insights here are also invaluable for undergraduates pursuing research grants, such as for a senior thesis.

Navigating the Grant Writing Journey

A grant proposal is essentially a persuasive document aimed at convincing an organization to invest in your research project. While grant writing approaches vary across disciplines—epistemological research in philosophy differs significantly from application-driven research in medicine—this guide offers a comprehensive framework applicable broadly.

Before you even start writing, clarity on your research and its purpose is paramount. You might have a fascinating topic, but articulating your ultimate goals is crucial to convince funders of your project’s worth. Even if you’re in humanities or arts, framing your project within the structures of research design, hypotheses, and expected outcomes is essential for funders. This process can also illuminate new dimensions of your research.

Crafting successful grant applications is a journey that starts with an idea and evolves cyclically, not linearly. Many begin by pinpointing their core research question. What new knowledge will your project unearth? Why is this research significant in a larger context? Clearly communicating this purpose is key to persuading the review committee. Knowing your destination before you embark on writing makes this communication much more effective.

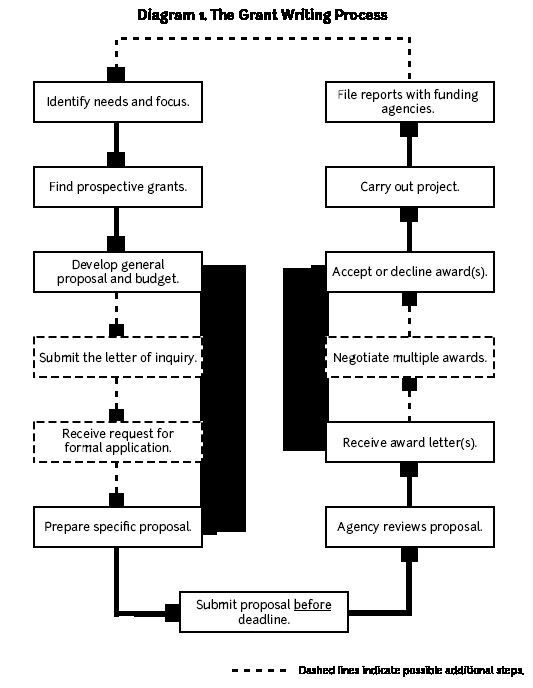

Diagram 1 offers a roadmap of the grant writing process to help you strategize your proposal development.

A chart labeled The Grant Writing Process that provides and overview of the steps of grant writing: identifying a need, finding grants, developing a proposal and budget, submitting the proposal, accepting or declining awards, carrying out the project, and filing a report with funding agencies.

A chart labeled The Grant Writing Process that provides and overview of the steps of grant writing: identifying a need, finding grants, developing a proposal and budget, submitting the proposal, accepting or declining awards, carrying out the project, and filing a report with funding agencies.

Applicants engage in a cycle: writing proposals, submitting them, receiving decisions, and revising based on feedback. Unsuccessful proposals are refined and resubmitted in subsequent funding cycles. Successful grants and the resulting research often pave the way for new research avenues and future grant proposals.

Building a strong, ongoing relationship with funding agencies can lead to further funding opportunities. Always submit progress and final reports promptly and professionally. Contrary to the fear that past funding might deter future grants, the opposite is often true: funding tends to attract more funding. A track record of successful grants enhances your competitiveness and future funding prospects.

Key Strategies for Grant Success

- Start Early: Grant writing is time-intensive. Begin well in advance of deadlines.

- Apply Widely and Persistently: Increase your chances by applying to multiple relevant grants and don’t be discouraged by rejections.

- Always Include a Cover Letter: A personalized cover letter adds a professional touch to your application.

- Address Every Question Thoroughly: Provide complete answers and anticipate potential reviewer questions proactively.

- Revise and Resubmit: Rejection is a learning opportunity. Refine your proposal based on feedback and try again.

- Tailor to Funder Priorities: Give them exactly what they are looking for by meticulously following application guidelines.

- Be Explicit and Specific: Clarity is key. Avoid ambiguity and provide detailed information.

- Design a Realistic Project: Ensure your proposed project scope and timeline are achievable.

- Show Clear Connections: Explicitly link your research questions, objectives, methods, results, and dissemination plans.

- Adhere to Guidelines (Again): Emphasizing this again – strict adherence to guidelines is critical for a successful application.

Pre-Writing: Setting the Stage for Funding

Defining Your Needs and Research Focus

Begin by clearly identifying your specific funding needs. Consider these questions to guide you:

- Is this for preliminary research to shape a larger research agenda?

- Are you seeking funds for dissertation, pre-dissertation, postdoctoral, archival, experimental, or fieldwork research?

- Do you need a stipend to focus on writing a dissertation, book, or polishing a manuscript?

- Are you pursuing a fellowship at an institution offering resources to enhance your project?

- Is your goal to fund a multi-year, large-scale research project with a team?

Next, sharpen the focus of your research project. Answering these questions can help refine your focus:

- What is your research topic? Why is it important and timely?

- What specific research questions are you addressing? What is their broader relevance?

- What are your working hypotheses?

- What research methods will you employ? Are they appropriate and innovative?

- What is the significance of your research? What impact will it have?

- Will you use quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods approaches?

- Is your research experimental or clinical in nature?

Once you have a clear understanding of your needs and research focus, you can start identifying potential grant opportunities and funding agencies that align with your goals.

Identifying the Right Funding Sources

Securing funding hinges significantly on aligning your research goals with the priorities of grant-awarding agencies. The effort spent in identifying suitable grantors pays off substantially in the long run. Even a brilliant proposal is unlikely to succeed if submitted to the wrong institution.

Numerous resources can help you find grant agencies and programs. Most universities and colleges have dedicated Offices of Research to assist faculty and students in their grant-seeking efforts. These offices often maintain libraries or resource centers to facilitate grant discovery.

For example, the Research at Carolina office at UNC (http://research.unc.edu) coordinates research support across the university. Their Funding Information Portal (https://fundingportal.unc.edu/) offers databases and proposal development guidance. Additionally, specialized offices exist within the UNC School of Medicine (https://www.med.unc.edu/oor/) and School of Public Health (http://www.sph.unc.edu/research/).

Crafting Your Proposal: Writing to Get Funded

Understanding Your Audience

Grant proposals are typically reviewed by academics with expertise in relevant disciplines or program areas. Therefore, write assuming your audience is a knowledgeable colleague in your field, but not necessarily deeply familiar with the specifics of your research.

Recognize that reviewers are often busy. A poorly organized, unclear, or poorly written proposal is unlikely to be well-received. Make it easy for reviewers to understand and appreciate your project. Always adhere to the specific guidelines of the grant you are applying for, even if it requires adjusting your project’s framing or language. Adapting your proposal to fit grant requirements is legitimate and often necessary, as long as it doesn’t compromise your core project objectives or outcomes.

Funding decisions often boil down to whether the proposal convinces reviewers that the research is well-conceived and feasible, and that the investigators are capable of executing it successfully. Be as explicit as possible throughout your proposal. Anticipate reviewer questions and address them proactively. Przeworski and Salomon (1995) highlight three key questions reviewers consider:

- What new knowledge will this project generate? (goals, aims, and outcomes)

- Why is this knowledge valuable? (significance)

- How will the validity of the findings be ensured? (criteria for success)

Ensure your proposal clearly answers these questions. Remember that reviewers might not read every word. They may focus on the abstract, research design, methodology, CVs, and budget. Make these sections exceptionally clear and compelling.

Writing Style: Projecting Competence and Clarity

Your writing style in a grant proposal reflects your scholarly persona (Reif-Lehrer 82). Reviewers will form impressions about your creativity, logic, analytical skills, field knowledge, and, most importantly, your capacity to complete the proposed project. While disciplinary conventions should guide your general style, let your unique voice and scholarly personality come through. Clearly articulate your project’s theoretical framework.

Developing a Core Proposal and Budget

Since you might seek funding from multiple sources, start by developing a general grant proposal and budget, sometimes termed a “white paper.” This foundational proposal should explain your project to a broad academic audience. Before submitting to specific grant programs, you’ll tailor it to their particular guidelines and priorities.

Structuring Your Proposal for Impact

While specific requirements vary by funding agency, several elements are typically standard in grant proposals, often in this order:

- Title Page

- Abstract

- Introduction (problem statement, research purpose/goals, significance)

- Literature Review

- Project Narrative (methods, procedures, objectives, outcomes/deliverables, evaluation, dissemination)

- Personnel

- Budget and Budget Justification

Format your proposal for readability. Use headings to divide sections. For longer proposals, include a table of contents with page numbers.

Title Page: Should include a concise, descriptive title, principal investigator names, institutional affiliations, funding agency name and address, project dates, funding amount requested, and authorizing signatures (if required). Adhere strictly to the funding agency’s title page specifications.

Abstract: This is your project’s first impression. It also serves as a quick reminder for reviewers during final recommendations. Summarize key project elements in the future tense, including: (1) general purpose, (2) specific goals, (3) research design, (4) methods, and (5) significance (contribution and rationale). Be explicit; use phrases like “The objective of this study is to…”

Introduction: Cover the essential aspects of your proposal: problem statement, research purpose, goals/objectives, and significance. The problem statement should provide context, rationale, and highlight the research need and relevance. How does your project build upon or differ from existing research? Are you using innovative methods or exploring new theoretical ground? Research goals/objectives should specify anticipated outcomes that directly address the identified problem. Focus on primary goals, reserving sub-objectives for the project narrative.

Literature Review: Many proposals require a literature review to demonstrate your preliminary research. It should be selective, critical, and demonstrate your evaluation of relevant works, not just an exhaustive list. For more guidance, refer to resources on crafting effective literature reviews (https://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/literature-reviews/).

Project Narrative: This is the core of your proposal. It should detail the project, including a thorough problem statement, research objectives/goals, hypotheses, methods, procedures, outcomes/deliverables, evaluation, and dissemination plan.

In the project narrative, preemptively address all potential reviewer questions. Leave no room for uncertainty. For instance, if you propose unstructured interviews, explain why this method is optimal for your research questions. If using item response theory, justify its advantages over classical test theory. If archival research in a remote location is necessary, clarify the specific documents you expect to find and their relevance to your project.

Clearly and explicitly connect your research objectives, questions, hypotheses, methodologies, and anticipated outcomes. As project narrative requirements vary by discipline, consult discipline-specific grant writing guides for additional advice.

Personnel: Detail staffing needs and justify them clearly. Be explicit about the skills of current personnel (include CVs). Describe necessary skills and roles for new hires. Optimize budget efficiency by phasing out personnel as their roles conclude.

Budget: The budget outlines project costs, typically as a spreadsheet with line items and a budget narrative (justification) explaining expenses. Always include a budget narrative, even if not explicitly required. Example #1 at the end of this guide provides a sample budget.

Consider creating a comprehensive budget, even if it exceeds a particular funder’s typical grant size. Indicate that you are seeking supplementary funding from other sources. This facilitates combining awards if you receive multiple grants.

Ensure all budget items comply with the funding agency’s regulations. For example, U.S. government agencies have specific travel requirements. Verify your budget aligns with these. If an item falls outside an agency’s coverage (e.g., equipment purchases), state in the justification that other funding sources will cover it.

Many universities require indirect costs (overhead) on grants. Confirm standard overhead rates with your university’s grant administration office. Consult them also for indirect costs and charges not directly research-related (e.g., facility fees).

Account for applicable taxes. Tax rates can vary based on expense categories and your circumstances (e.g., foreign national status). Consult university staff or tax professionals. For scholarship and fellowship tax information, see https://cashier.unc.edu/student-tax-information/scholarships-fellowships/.

Timeframe: Provide a detailed project timeline, outlining start and completion dates for each phase. A visual timeline can be helpful for reviewers. For simpler projects, a table summarizing the timeline is effective. See Example #2. For complex, multi-year projects, a timeline diagram can enhance clarity and demonstrate feasibility. See Example #3.

Refining Your Proposal: The Path to “Yes”

Developing strong grant proposals is a lengthy process. Start early to allow time for feedback from multiple reviewers on different drafts. Seek feedback from specialists in your area and non-specialist colleagues. Request targeted feedback on specific sections; for example, consult a statistician for methodology review. Utilize campus research offices. At UNC, the Odum Institute (https://odum.unc.edu/) offers various services to social science researchers.

During revision, ask reviewers to focus on the clarity of connections between research objectives and methodology. Use these questions to guide feedback:

- Is the case for funding compelling?

- Are hypotheses clearly stated?

- Is the project feasible, or overly ambitious? Are there weaknesses?

- Are the success criteria for project evaluation clear to funders?

If the funding agency provides proposal evaluation criteria, share these with your reviewers.

Example #1. Sample Budget

| Item | Qty | Cost | Subtotal | Total | |

| Jet Travel | |||||

| RDU-Kigali (RT) | 1 | $6,100 | $6,100 | ||

| Maintenance | |||||

| Rwanda | 12 months | $1,899 | $22,788 | $22,788 | |

| Project | |||||

| RA/Translator | 12 months | $400 | $4,800 | ||

| Transport-In-Country | |||||

| Phase 1 | 4 months | $300 | $1,200 | ||

| Phase 2 | 8 months | $1,500 | $12,000 | ||

| 12 months | $60 | $720 | |||

| Audio Tapes | 200 | $2 | $400 | ||

| Photo/Slide Film | 20 | $5 | $100 | ||

| Laptop | 1 | $2,895 | |||

| Software | NUD*IST 4.0 | $373 | |||

| Etc. | |||||

| Total Project Allowance | $35,238 | ||||

| Admin Fee | $100 | ||||

| Total | $65,690 | ||||

| Other Sources | Sought from other sources | ($15,000) | |||

| Total Grant Request | $50,690 |

Jet travel $6,100: Based on commercial high season economy fare on Sabena Belgian Airlines (no U.S. carriers to Kigali). Student fares are significantly lower (approx. $2,000).

Maintenance allowance $22,788: Based on Fulbright-Hays maintenance rates.

Research assistant/translator $4,800: Native Kinya-rwanda speaker with a university degree, assisting with life history interviews and participant observation. $400/month based on NGO rates in Rwanda.

Transportation within country, phase one $1,200: Local transport in Kigali (bus/taxi), approx. $10/day.

Transportation within country, phases two and three $12,000: Transport between rural sites, 4×4 rental at $130/day, estimated $50/day average. Could be reduced with government/aid agency transport assistance.

Email $720: RwandaTel service at $60/month, essential for news and communication with advisors.

Audiocassette tapes $400: For recording interviews, performances, events, etc.

Photographic & slide film $100: Documenting visual data (landscape, events, etc.).

Laptop computer $2,895: For recording observations and analysis, UNC student special offer price.

NUD*IST 4.0 software $373.00: For cataloging and managing field notes, indexing themes in interviews.

Administrative fee $100: Fulbright-Hays fee for sponsoring institution.

Example #2: Project Timeline in Table Format

| Phase | Status |

|---|---|

| Exploratory Research | Completed |

| Proposal Development | Completed |

| Ph.D. Qualifying Exams | Completed |

| Research Proposal Defense | Completed |

| Fieldwork in Rwanda | Oct 1999-Dec 2000 |

| Data Analysis & Transcription | Jan 2001-Mar 2001 |

| Draft Chapter Writing | Mar 2001-Sep 2001 |

| Revision | Oct 2001-Feb 2002 |

| Dissertation Defense | April 2002 |

| Final Approval & Completion | May 2002 |

Example #3: Project Timeline in Chart Format

[Example #3: Project Timeline in Chart Format from original document]

Final Thoughts: Just Ask!

Asking for funding can feel daunting. Feelings of self-doubt are common, but remember, it never hurts to ask. If you don’t ask for the money, you definitely won’t get it. The worst outcome is a “no,” which is just an opportunity to revise and try again.

UNC Proposal Writing Resources

Research at Carolina http://research.unc.edu

The Odum Institute for Research in the Social Sciences https://odum.unc.edu/

UNC Medical School Office of Research https://www.med.unc.edu/oor

UNC School of Public Health Office of Research http://www.sph.unc.edu/research/

Works Consulted

[List of Works Consulted from original document]

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill