The Olympic Games showcase the pinnacle of athletic achievement, where elite competitors display extraordinary skill and dedication before a global audience. While mainstream sports like basketball and tennis enjoy year-round prominence, the Olympics elevate niche disciplines such as artistic swimming, breaking, and table tennis, offering them a rare moment in the limelight.

However, for many Olympians, particularly those in less commercially viable sports, sustaining a career beyond the Games presents significant financial hurdles. Unlike athletes in major professional leagues, lucrative endorsement deals and multi-million dollar contracts are not typically on the table. While the United States Olympic and Paralympic Committee does reward athletes with cash prizes for medals – $37,500 for gold, $22,500 for silver, and $15,000 for bronze – this often isn’t enough to live on, especially considering the intensive training required.

To make ends meet, many Olympic athletes juggle their rigorous training schedules with various income-generating activities. This article, drawing insights from athletes in artistic swimming, breaking, and table tennis, explores the diverse revenue streams Olympians tap into to support their athletic dreams and daily lives. Despite the financial challenges, these athletes express optimism about the growing opportunities within their sports and evolving pathways to financial stability.

Diving into Dollars: How Artistic Swimmers Earn

Artistic swimming, a mesmerizing blend of athleticism and artistry, captivated audiences at the Paris Olympics, where the U.S. team clinched a silver medal – their first Olympic medal since 2004. For elite artistic swimmers dedicated to Olympic-level national teams, training is a full-time commitment.

Anita Alvarez, a three-time Olympian and silver medalist from the Paris Games, explains the financial structure for national team members. Athletes receive a stipend from the U.S. Olympic Committee, which provides a foundational level of support. When Alvarez first joined the national team, this stipend was modest, around $200 to $300 per month.

“Now, based on how many Olympics you’ve been to, how many world championships, things like that, you’ll get more,” she stated. Currently, her monthly stipend is approximately $2,000, reflecting her experience and achievements.

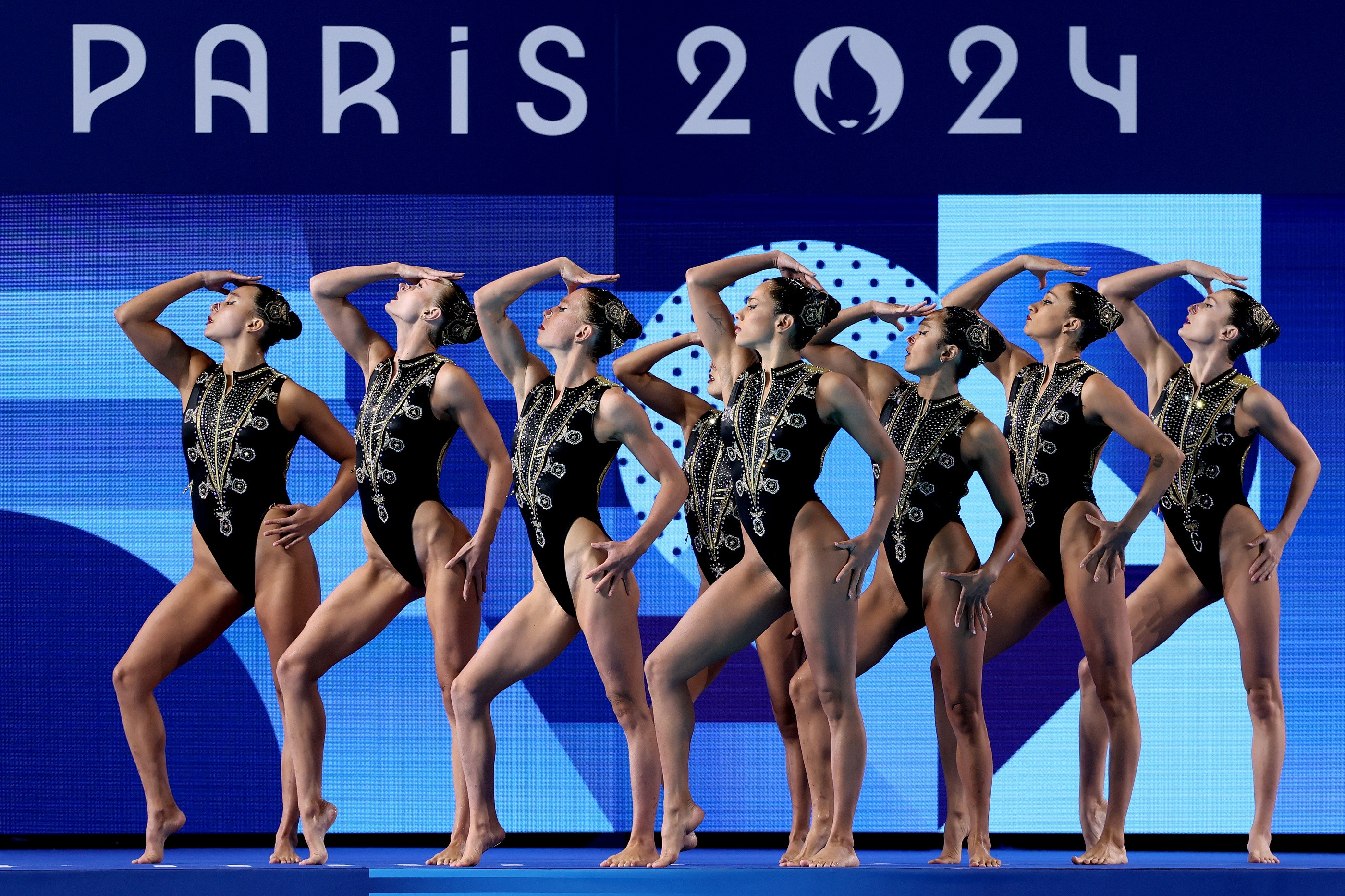

Members of the U.S. artistic swimming team competing at the 2024 Olympic Games.

Members of the U.S. artistic swimming team competing at the 2024 Olympic Games.

Beyond stipends, prize money from major competitions like the World Aquatics Championships offers another income avenue. First-place finishers in solo and duet events at the 2024 championships, for instance, received $20,000.

However, even with increased stipends and competition winnings, artistic swimmers often need to supplement their income. Alvarez, who moved to California at 16 to train full-time, acknowledges the constant financial balancing act, especially in a state with a high cost of living.

Coaching and Private Lessons: One common revenue stream for artistic swimmers is coaching. Alvarez coaches club teams, where rates can start around $30 per hour. Private lessons offer more flexibility, allowing coaches to set their own, often higher, rates.

Social Media and Content Creation: The rise of platforms like Instagram and TikTok has opened up unexpected financial opportunities. Alvarez highlights her teammate Daniella Ramirez, who gained significant traction with TikTok videos showcasing artistic swimming hair management techniques.

“She, since then, has been making a living, basically, off of her TikTok and Instagram reels,” Alvarez noted. Ramirez’s social media success has not only benefited her personally but has also increased visibility for artistic swimming.

Entertainment Industry Gigs: Artistic swimmers possess unique aquatic skills that are highly sought after in the entertainment industry. Alvarez points to opportunities in water-based performances for parties, music videos, commercials, weddings, Cirque du Soleil shows, and movies. One-off shows can earn around $300, while larger projects like commercials or film work can yield significantly more, sometimes reaching $10,000.

Alvarez herself participated in underwater stunt work for the film “Black Panther: Wakanda Forever,” demonstrating the diverse earning potential in entertainment. However, balancing these gigs with rigorous training is challenging. Alvarez recalls working late nights at a sporting goods store for three years after her first Olympics to make ends meet.

Janet Redwine, a 2008 Olympic artistic swimmer, emphasizes the importance of family support for many athletes during their demanding training years. Post-competition, coaching remains a popular way for former artistic swimmers to stay connected to the sport and earn income, as Redwine herself did. She now utilizes her athletic discipline and experience as the director of program success at the University of Denver’s Daniels College of Business.

Alvarez is optimistic about the future of artistic swimming, noting increased recognition of the sport’s difficulty and artistry. The team’s viral moonwalking routine at the 2024 Olympics, set to Michael Jackson’s “Smooth Criminal,” generated widespread positive attention.

While Alvarez has engaged in short-term brand collaborations, her goal is to establish longer-term partnerships, recognizing the multifaceted potential of artistic swimmers as athletes, artists, performers, and entertainers.

Breaking Barriers and Banks: Income Streams for Breakers

Breaking, or breakdancing, made a historic debut at the recent Summer Olympics, injecting youthful energy and urban culture into the Games. Sunny Choi, a U.S. B-girl who competed in breaking’s Olympic premiere, emphasized the necessity of diverse income streams for breakers beyond competitions in a 2022 interview with Boardroom.tv.

“Many breakers have dance studios, teaching, or a side job,” Choi explained. “[Breakers will] have other side hustles or things to supplement.”

B-Girl Sunny Choi competed at the Olympics’ first-ever breaking competition.

B-Girl Sunny Choi competed at the Olympics’ first-ever breaking competition.

Similar to artistic swimmers, breakers can find performance opportunities in Cirque du Soleil shows, commercials, and hip-hop theater productions. However, relying solely on competition winnings for a sustainable living is unrealistic for most, according to Ian Flaws, founder and director of The Bboy Factory, a breaking studio in Denver.

“I always tell my students you can’t really rely on winning a competition to pay your rent. There’s always a bigger, badder dude out there,” Flaws advises, highlighting the competitive and unpredictable nature of prize money.

Competition Prize Money: While some competitions offer modest prizes, like $1,000 for winning teams (split amongst members), higher-stakes events can offer up to $15,000 for individual winners, as noted by Flaws.

Teaching and Dance Studios: A more stable income path for breakers lies in teaching. Flaws estimates that breakers combining competitive events with teaching or side hustles can earn between $25,000 and $100,000 or more annually. The growth of breaking’s popularity has fueled the establishment of dedicated studios and educational facilities. When Flaws opened his studio in 2012, only a handful existed in the U.S.; now, most major cities have at least one.

Dance teacher earnings vary based on experience and class type, ranging from $30 to $200 per hour. Private lessons can command $60 to $100 per hour.

Brand Sponsorships and Endorsements: Corporate interest in breaking is on the rise. Victor Montalvo, a U.S. B-boy Olympic bronze medalist, served as an ambassador for Delta Air Lines during the Paris Games. Jack in the Box has sponsored breaking events, and Nike released its first breaking-specific shoes ahead of the Olympics, signaling growing mainstream recognition. Long-term supporters like Red Bull, creator of the Red Bull BC One competition, have also played a crucial role in the breaking scene.

Despite breaking not being slated for the 2028 Olympics, Flaws believes its global popularity will continue to expand. Even Olympic breakers who didn’t medal, or faced criticism, may find new opportunities. Australian B-girl Rachael Gunn (RayGun), who went viral for her Olympic performance, could leverage her newfound fame for speaking engagements or reality TV, according to Dee Madigan, executive creative director at Campaign Edge. Madigan suggests brands might even seek to feature her in advertisements, demonstrating that even unexpected attention can translate into income.

Table Tennis Tactics: Making a Living in Ping Pong

Table tennis Olympian Kanak Jha achieved a historic milestone at the Summer Games, reaching the final 16 – the furthest a U.S. men’s player has ever advanced. Yet, even a top-tier athlete like Jha has faced significant financial challenges, resorting to crowdfunding to support his career. In April, he launched a GoFundMe campaign to cover training, travel, coaching, and other essential expenses, raising over $30,000.

“It’s impossible to be a professional table tennis player living in the U.S. Financially, it’s impossible,” Jha told The Associated Press, underscoring the financial realities of pursuing professional table tennis in the United States.

Kanak Jha (left) returns the ball to Moldova’s Vladislav Ursu during the men’s table tennis singles preliminary round at the Paris 2024 Olympic Games.

Kanak Jha (left) returns the ball to Moldova’s Vladislav Ursu during the men’s table tennis singles preliminary round at the Paris 2024 Olympic Games.

Tournament Prize Money: While tournaments offer prize money, relying on competition winnings is a gamble, explains Sean O’Neill, a two-time Olympian and president of the U.S. Table Tennis Hall of Fame. Serious players often compete monthly, but expenses like airfare, accommodation, and food can negate winnings if performance is poor.

The U.S. Open and U.S. National Table Tennis Championships, both five-star events, offer $10,000 and $5,000-$8,000 for Men’s and Women’s Singles winners, respectively. Four-star events offer $1,000 to $2,500 for Open Singles. Stars indicate prize money, table quantity, and playing conditions, with five-star events being the highest tier.

Sponsorships and Equipment Deals: Equipment companies are primary sponsors in table tennis. Players with signature paddles may earn commissions on sales, or national team members might secure brand representation deals worth $10,000 to $20,000 annually, according to O’Neill.

Coaching and Camps: Similar to artistic swimming and breaking, coaching and running table tennis camps are supplementary income sources. Camps can generate $500 to $1,000 per day, while hourly coaching rates range from $50 to $150. However, O’Neill points out the trade-off: “The problem with that is you’re not training if you’re coaching.”

Corporate and Media Opportunities: Corporations hire players for meet-and-greets, and organizations like the PGA Tour have engaged table tennis players for athlete entertainment. Former Olympians like O’Neill can also earn income as commentators for media coverage, such as NBC’s Olympic broadcasts.

European Leagues and Global Disparities: Europe presents a more lucrative table tennis landscape, with top male league players earning $50,000 to over $100,000, and top female players earning $30,000 to $40,000 annually, according to O’Neill. Including sponsorships, top European male players can reach incomes between $100,000 and $750,000. Government support also varies globally; Chinese Olympic gold medalist Chen Meng reportedly received $525,000 from China for her Paris victory.

Emerging Professional Leagues: The landscape is evolving, with the U.S. launching its first professional table tennis league last year, Major League Table Tennis, offering player compensation, though amounts are undisclosed. Table tennis clubs are also growing, providing structured training for young players. O’Neill reflects on the sport’s development since his youth, noting the increased accessibility of training and competition within the U.S.

Conclusion: The Evolving Economics of Olympic Dreams

For Olympians in niche sports, making money is a multifaceted endeavor demanding creativity, resilience, and entrepreneurial spirit. While medal prizes and Olympic stipends offer some financial support, they rarely suffice for a sustainable career. Athletes commonly diversify their income through coaching, entertainment gigs, social media, sponsorships, and, in some cases, crowdfunding.

The financial realities vary significantly across sports and geographical locations. While challenges persist, there’s a growing sense of optimism. Increased media attention, rising corporate interest, and the emergence of professional leagues are gradually expanding financial opportunities for Olympic athletes, paving the way for a more sustainable future for those dedicated to pursuing their Olympic dreams.