Returning from Miami, the stark reality of the Untitled Art Fair hits home as I tally expenses against income. This year marks our third participation, and unfortunately, our first financial loss. For a small Midwestern gallery like ours, these major art fairs—Untitled in Miami and the Outsider Art Fair in New York—are crucial. They can generate a quarter of our annual revenue and, more importantly, cultivate a national collector base for the regional artists we champion. Survival in this business hinges on these events.

Participating in curated international fairs like Untitled is a significant investment. Our modest 14 x 14-foot booth cost $17,400. Factoring in staff accommodation, transportation, meals, and additional framing, the total expenditure climbed to approximately $30,000.

This year, the math didn’t add up. We ended up in the red, a painful first.

After days of sluggish sales, conversations with other gallery owners revealed a shared experience. The art market has been experiencing a downturn for the past two years. The reasons remain unclear—speculations range from stock market volatility to the global impact of wars and natural disasters, the shrinking middle class, escalating art prices, and rising inflation. An Artnews report hinted at revenue drops exceeding 50% for many galleries compared to the previous year, with auction giants like Sotheby’s and Christie’s also reporting substantial declines. The sentiment is clear: the “Money Art” market is facing a significant challenge.

View of the aisles at Untitled Art Fair

View of the aisles at Untitled Art Fair

A gallery director friend from Los Angeles echoed this sentiment over dinner, admitting that absorbing further losses was unsustainable after two difficult years. Inquiring about a smaller New York gallery, the news was equally grim.

Uncertainty is inherent in the “money art” world. Sales bring an exhilarating, almost addictive high, validating the often-questionable sanity of this profession. Conversely, slow sales can deflate spirits. Robust sales affirm the viability of producing and selling art, suggesting that artists can indeed make a living creating, and that the entire ecosystem—artists, dealers, curators, institutions, collectors, and critics—is a vibrant, interconnected world fueled by passion and belief. Those immersed in this world cling to the idea that art embodies the best of humanity, offering a tangible reflection of open-mindedness, rigor, and exploration.

The world arguably needs art, but the intense commercial nature of major art fairs can compromise its inherent integrity. When the “money art” slows down, the art world can feel precarious, and the art itself can start to seem like frivolous luxury items for the wealthy.

At Untitled, 171 galleries from across the globe showcased carefully curated works within a sprawling tent structure on the beach. White walls and bright lighting accentuated the seductive elements of the art on display: monumental scale, polished surfaces, and evident displays of skill and labor, from photorealistic paintings to intricate sculptures.

The author during the take-down of Portrait Society Gallery’s booth at Untitled Art Fair (2024)

The author during the take-down of Portrait Society Gallery’s booth at Untitled Art Fair (2024)

During lulls in booth traffic, observing the crowd became a repetitive exercise. To distract from the anxiety of hoping someone would connect with our artists’ work and budget, I turned my attention to the art itself. I found solace in remembering that each piece originated in the quiet solitude of an artist’s studio, born from struggle, contemplation, and dedication, intertwined with pride, skill, and intellect. Focusing on these details felt grounding, like reconnecting with familiar comforts amidst the fair’s pressures.

Yet, the persistent question lingered: “Why am I doing this?” Few professions operate on such unstable foundations. It takes an emotional toll. Then, a sudden realization: the very unpredictability of this “money art” business is also its allure. Uncertainty breeds possibility. Nothing is routine or fully controlled, meaning each new project, catalog essay, art fair, or exhibition can bring fresh perspectives, discoveries, and the privilege of sharing this unique world.

At these fairs, art transitions from the artist’s studio to the dealer’s hands, ideally ending up in a collector’s home. Gallerists are tasked with re-imbueing these objects with their human essence through information, context, and persuasive communication. Visitors often express gratitude for the time spent engaging with them, valuing the direct interaction.

However, this connection doesn’t always translate into immediate financial returns within the “money art” framework. At our booth, the artist who generated near sell-out sales at last year’s preview saw significantly fewer sales this year. For the first three days, inquiries about the handmade designer furniture in our booth outnumbered those about the art on the walls.

Meg Lionel Murphy, “Mad Girls Love Song” (2024), acrylic and acrylic gouache on paper, 72 x 48 inches (182.9 x 121.9 cm) (image courtesy the author)

Meg Lionel Murphy, “Mad Girls Love Song” (2024), acrylic and acrylic gouache on paper, 72 x 48 inches (182.9 x 121.9 cm) (image courtesy the author)

Saturday and Sunday were anticipated to improve fair traffic. Saturday yielded only a minor sale. Sunday, the final day, quietly slipped away, its five-hour promise unfulfilled until near closing. Then, a couple entered our booth, captivated by a large canvas by a young Midwestern artist. We engaged in conversation, sharing insights about the piece. The painting of sword-wielding giant women in a medieval setting resonated with them, reminding them of their three daughters. They purchased it—our first five-figure sale of the fair. While not enough to break even, it softened the financial blow.

At 5 pm on Sunday, after six days of business transactions within this “money art” ecosystem, a rapid deconstruction consumed the fair. Dealers, moments before exuding sophistication, were now on the floor with tape and bubble wrap, maneuvering artworks into shipping crates for journeys across continents. The sounds of packing tape and plastic wrap filled the air—a familiar, urgent rhythm of this profession. White-gloved handlers joined exhausted dealers in the packing process. It’s a peculiar life, I reflected, both refined and rugged, intellectual and practical. In a small gallery like ours, the owner and a single staff member handle curating, installation, repairs, shipping, marketing, website updates, press releases, newsletters, and client relations. Most small galleries operate on thin margins. In the Midwest, many gallerists rely on supplementary income streams to sustain their passion for “money art”.

Instagram updates revealed that my Los Angeles gallery friend, who initially faced similar slow sales, experienced a turnaround by the fair’s end. I was genuinely happy for her.

Before heading to the airport, I visited the Perez Museum to meet a friend. Stepping inside, a wave of anxiety washed over me, a stark contrast to the intended escape. The sheer volume of art felt overwhelming. I confessed to my friend, an art historian, that I was struggling to engage. She understandingly suggested a casual stroll. She paused at a Carmen Herrera painting, “Alba” (2014). I wished I could fully appreciate her insights on this celebrated Cuban-born artist who lived to 106. Herrera’s bold, simple geometric abstraction felt vibrant, but I couldn’t fully connect. The injustice of Herrera’s late recognition, selling her first painting at 89 when the “money art” market finally aligned with her, resonated deeply. The art world mirrors broader societal inequities, often masked by art world jargon.

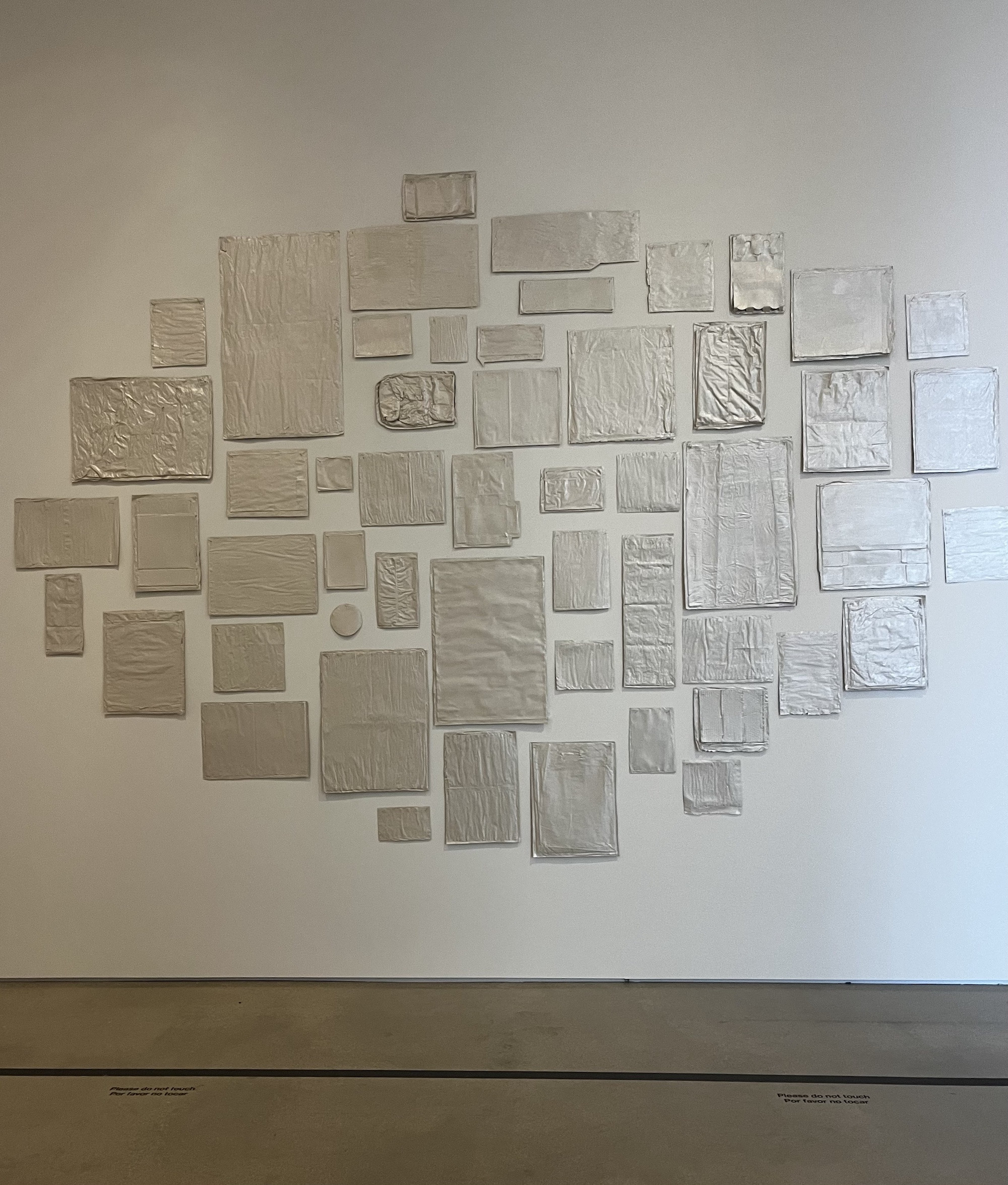

Installation view of Abraham Cruzvillegas, “Blind self portrait listening to ‘Our delight’ by Dizzie Gillespie, watching some nice videos -sent by Isadora Hastings- of Garifuna ladies dancing in frenzy during a ceremony in Trujillo, Honduras, after reading Emiliano Monge’s ‘La superficie más honda’” (2017), enamel on newspaper clippings, cardboard, photographs, drawings, postcards, envelopes, tickets, vouchers, letters, drawings, posters, flyers, cards, recipes, napkins, and steel pins

Installation view of Abraham Cruzvillegas, “Blind self portrait listening to ‘Our delight’ by Dizzie Gillespie, watching some nice videos -sent by Isadora Hastings- of Garifuna ladies dancing in frenzy during a ceremony in Trujillo, Honduras, after reading Emiliano Monge’s ‘La superficie más honda’” (2017), enamel on newspaper clippings, cardboard, photographs, drawings, postcards, envelopes, tickets, vouchers, letters, drawings, posters, flyers, cards, recipes, napkins, and steel pins

Drifting through the museum, every artwork felt daunting until we entered a room featuring rectangular shapes covered in silver. The artist was unfamiliar, but I paused. The shapes were repurposed mailers and packaging. These humble materials felt like a relief from the week’s intense focus on high-value “money art”. Perhaps it was the juxtaposition of discarded materials and the silver sheen, or maybe Abraham Cruzvillegas’s piece embodied transformation while retaining fragments of the everyday. In front of his work, my spirit felt a subtle return, a sense of rediscovery within the demanding “money art” world.

Soon, unsold artworks would be en route back to Wisconsin, driven by my son, the gallery manager. A 26-hour drive through varying weather conditions.

Back at the gallery, a text message arrived—an inquiry about our most significant piece from the fair. It remained under consideration. Fingers crossed, we wait in the unpredictable currents of “money art”.