“Money, money, money, must be funny, in the rich man’s world.” The ABBA lyric, ironic and catchy, sets a stage for considering Martin Amis’s novel Money, a book recently dissected by my book club. Following our reading of Hernan Diaz’s Trust, we turned to Amis, prompted partly by his recent passing and the renewed discussions around his work. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given our group is composed entirely of women, and, shall we say, seasoned readers at that, Money proved to be a divisive choice. It’s rare that our collective gender identity plays such a central role in our reading experience, though D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover comes to mind as a notable, albeit contrasting, example. Ultimately, it’s safe to say, Money didn’t win us over. In fact, for most of us, reading it was an actively unpleasant experience. There was even a fleeting, jokingly morbid suggestion of book burning post-discussion – a testament to the strength of our reactions.

Our collective unease wasn’t solely directed at John Self, Money’s protagonist – a character so deeply obscene, offensive, ridiculous, and frankly, pathetic. We are seasoned enough readers to differentiate between a novel and its first-person narrator, especially when, as in this case, the author’s intention to make Self despicable is so glaringly obvious. Amis isn’t subtle in establishing this distance, almost preemptively ensuring we don’t misinterpret any endorsement of John Self’s worldview. As a character within the novel pontificates, “The distance between author and narrator corresponds to the degree to which the author finds the narrator wicked, deluded, pitiful, or ridiculous.” We grasped this authorial distance early on, yet found ourselves trapped in Self’s obnoxious company for over four hundred pages. While plot twists do emerge, potentially complicating our relationship with him, and he arguably gains a sliver of sympathy as he becomes a scapegoat for the broader machinations of avaricious 1980s figures, the journey remained arduous. Glimmers of self-awareness and self-criticism flicker, hinting at a depth beyond simple self-loathing. “Look at my life,” Self challenges,

I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking: But it’s terrific! It’s great! You’re thinking: Some guys have all the luck! Well, I suppose it must look quite cool, what with the aeroplane tickets and the restaurants, the cabs, the filmstars, Selina, the Fiasco, the money. But my life is also my private culture—that’s what I’m showing you, after all, that’s what I’m letting you into, my private culture. And I mean look at my private culture. Look at the state of it. It really isn’t very nice in here. And that is why I want to burst out of the world of money and into—into what? Into the world of thought and fascination. How do I get there? Tell me, please. I’ll never make it by myself. I just don’t know the way.

Subtitled “A Suicide Note,” the novel foreshadows Self’s descent into despair and abjection. Moments of dark humor punctuate the narrative, and on a purely sentence-level, Amis’s prose can be undeniably virtuosic.

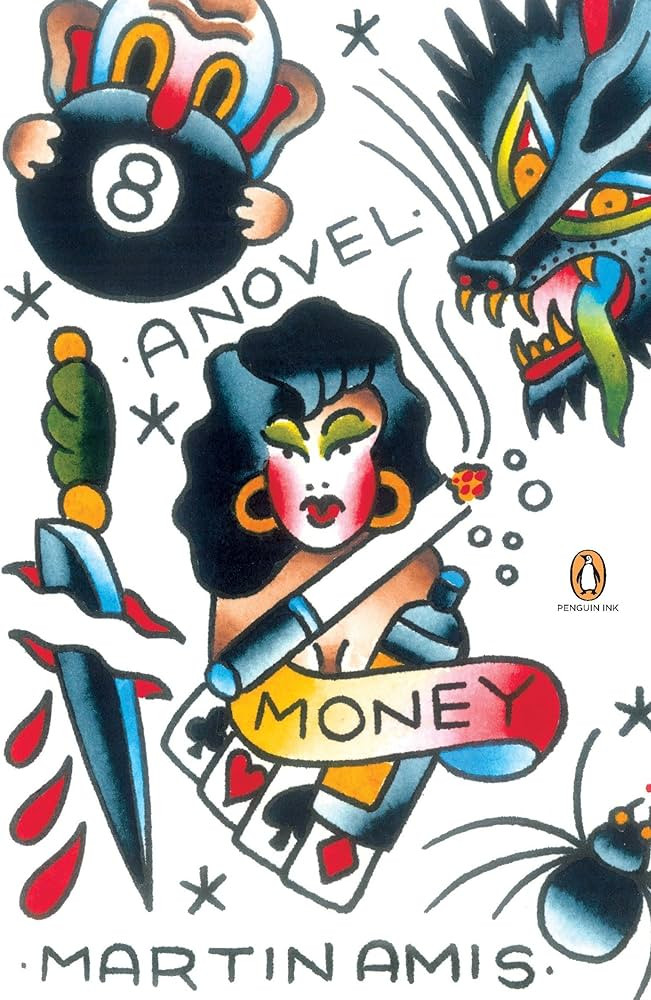

money-penguin-ink

money-penguin-ink

However, the substance of these sentences, their purpose and direction, became the central point of contention for me and many in my book club. What are we, as readers, truly invited to engage with when immersed in Money? To what extent does “comic effect” justify the relentless stream of offensive pronouncements and actions attributed to Self, presented for our supposed entertainment? What kind of authorial presence, even if we temporarily separate it from Amis himself, assumes we will find humor not only in Self’s operatic ineptitude but also in his attempted sexual assault? Is prolonged exposure to a monologue rife with sexism, racism, and bigotry truly engaging or rewarding, regardless of its rhetorical energy? We understand the satirical intent; John Self is an anti-hero, meticulously exposed in his depravity. The novel positions itself within the realms of satire – Rabelaisian, Swiftian, take your pick of literary poison. But it is poisonous, and there’s an undeniable undercurrent of self-congratulatory “bad boy” bravado in Amis’s approach. The metafictional cleverness feels like a safety net, a fallback in case the “it’s just a joke” defense falters. The book’s popularity, predominantly among male readers as far as we could discern, is unsettling. It suggests an uncomfortable number of men find vicarious pleasure in indulging the very demeaning, exploitative, and offensive attitudes they likely know better than to voice publicly. We recounted countless tedious experiences of challenging sexism in conversations with men, or in media consumed alongside them, only to be met with dismissal, silencing, or the ubiquitous “it’s just a joke” retort. The role of feminist killjoy is one we’d rather avoid, but the alternative is passive acceptance. Collectively, we have navigated enough real-world encounters mirroring John Self’s transgressions against women to find any humor in his shamelessness. We require no fictional reminders of how reprehensible such behavior is. What meaningful social, moral, or intellectual insight can possibly emerge from engaging with these issues through the lens of John Self?

Our discussion wasn’t entirely condemnatory. One member acknowledged John Self as a profoundly memorable, even iconic character. Reluctantly, we conceded that, despite our aversion, his execution was indeed brilliant. His voice, identified by Amis himself as the novel’s cornerstone, is undeniably distinctive and unforgettable. Perhaps our desire to erase it from memory is, as some might argue, our failing, not the novel’s. Money sparked a broader debate about the boundaries of offensive characters in fiction. We drew parallels with the morally bankrupt characters of Succession, questioning whether Self is inherently more objectionable. We agreed that Money would likely fail if told from an external perspective. Any engagement or nascent sympathy we felt for Self stemmed entirely from our immersion in his point of view. This immersion became a test of Amis’s experiment – how far could he push us before losing us entirely? We all persevered to the end, though strategic skimming was a common tactic when the narrative became too oppressive. Our discussion was certainly animated. However, none of us anticipate revisiting Amis’s oeuvre anytime soon. Interestingly, we fondly recalled reading his father Kingsley Amis’s Ending Up years prior, a book we collectively enjoyed.

In search of a feminist counterpoint, I proposed Diane Johnson’s The True History of the First Mrs. Meredith, inspired by a compelling episode about it on the Backlisted podcast. The suggestion was met with unanimous enthusiasm. This will be our next literary exploration, likely in the new year, offering a welcome palate cleanser after the disquieting world of John Self and the questionable humor of money.