Brazil’s journey from a modest exporter of tropical goods to a global agricultural giant is a remarkable economic transformation. Once known for coffee, sugar, and cacao in the mid-20th century, Brazil now rivals the United States as a leading supplier of soybeans, corn, cotton, and meat. This ascent is deeply rooted in Brazil’s macroeconomic policies, particularly those concerning Brazil Money, which have strategically shaped its agricultural sector’s competitiveness. Government interventions through credit, tax incentives, and pricing strategies have been instrumental in stimulating agricultural growth and boosting Brazilian exports on the world stage.

The foundation of Brazil’s agricultural boom was laid in the 1960s with a development strategy focused on tropical-suited agricultural technologies. Significant fiscal and financial support from the Brazilian government throughout the 1970s and 1980s, notably through subsidized credit programs, further propelled the sector. From the mid-1990s onwards, rising global commodity prices coincided with investment-driven growth in Brazilian agriculture. This period saw increased foreign investment and the growing influence of multinational corporations in both agricultural production and food processing, solidifying Brazil’s position in the global market.

Economic reforms post-1994, characterized by trade liberalization and flexible exchange rate policies, created a fertile environment for Brazilian agriculture. A more stable and open economy allowed Brazil to capitalize on government-backed research into crop and livestock varieties adapted to the Cerrados, the Brazilian savannah. Expanding its agricultural frontier into this vast tropical plain, Brazil rapidly became a top global producer of soybeans, corn, cotton, and meat. The early 21st century saw continued government efforts to enhance agricultural competitiveness by lowering production costs, improving market access, and investing in infrastructure. These developments cemented agriculture as a cornerstone of the Brazilian economy. In 2019, primary agricultural production contributed 8 percent to Brazil’s GDP, while the broader agro-industrial sector accounted for a substantial 32 percent.

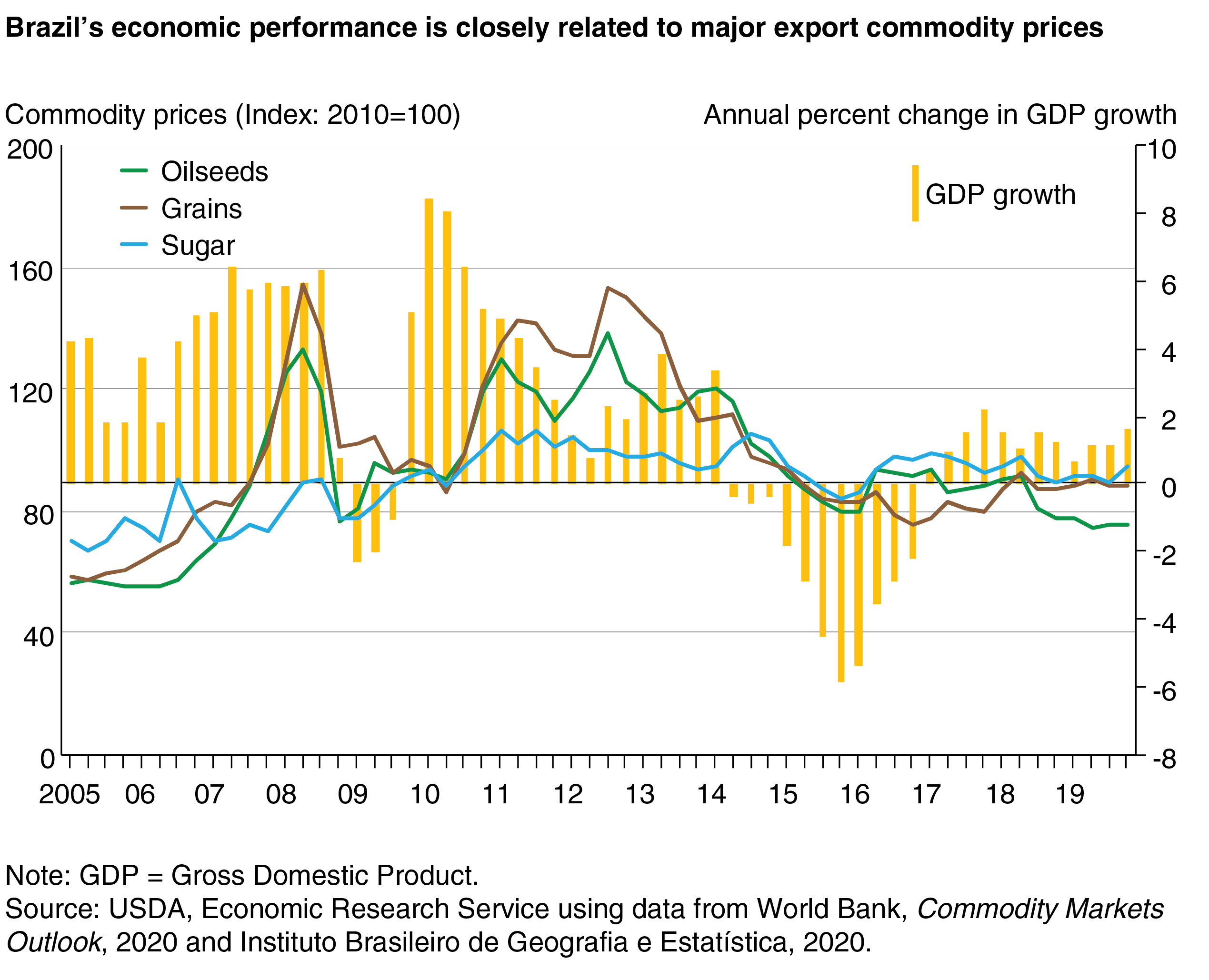

A bar graph of Brazil’s GDP growth annually from 2005-19 with line graphs of commodity prices for oilseeds, grains, and sugar.

A bar graph of Brazil’s GDP growth annually from 2005-19 with line graphs of commodity prices for oilseeds, grains, and sugar.

The period from 2005 to 2011 was a golden era for the Brazilian economy, fueled by surging commodity prices and readily available, low-interest international credit. However, the subsequent drop in commodity prices in 2012 for key Brazilian exports like soybeans and sugar led to an economic slowdown and eventual downturn. During this period of declining global commodity prices, the Brazilian government increased rural credit subsidies to counteract shrinking private credit, aiming to maintain production incentives and profitability. This strategic intervention allowed Brazil to continue expanding production and exports, even amidst lower prices, and further diversify its export markets.

Brazil’s economic history is marked by volatility and recurrent crises. The recession from mid-2014 to 2016 was particularly severe, with GDP shrinking by 3.8 percent in 2015 and 3.5 percent in 2016. Despite these challenges, the agricultural sector demonstrated remarkable resilience. The economy began a slow recovery in 2017, with GDP growth of 1.3 percent in both 2017 and 2018, followed by 1.1 percent in 2019.

Despite the broader economic headwinds, the agricultural sector’s continued production increases and yield growth during the 2014-16 recession played a crucial role in supporting GDP. By stimulating related industries like fertilizer and machinery, agriculture acted as an economic engine, offsetting contractions in the industrial and service sectors. Increased foreign investment in crop production, fertilizer development, and technology transfer further contributed to improved yields and higher agricultural output, underscoring the sector’s strength even during economic hardship.

This resilience enabled the agricultural sector to capitalize on growing export opportunities, particularly the rising demand for animal feed in China and other international markets. Brazil’s soybean production is now nearly on par with the United States, with each country accounting for roughly a third of global production. Brazil is also the world’s third-largest corn producer, contributing about 8 percent of global output.

How Brazil Money Policies—Currency Depreciation—Boost Exports

Exchange rate policies, a critical aspect of brazil money management, have significantly influenced Brazil’s agricultural export performance. Brazilian commodity exports are priced in U.S. dollars. When the Brazilian currency, the Real (BRL), depreciates, Brazilian producers can sell their goods at higher prices in local currency while remaining competitive in dollar terms on the global market. This currency depreciation incentivizes increased agricultural output and exports, potentially leading to lower international commodity prices overall.

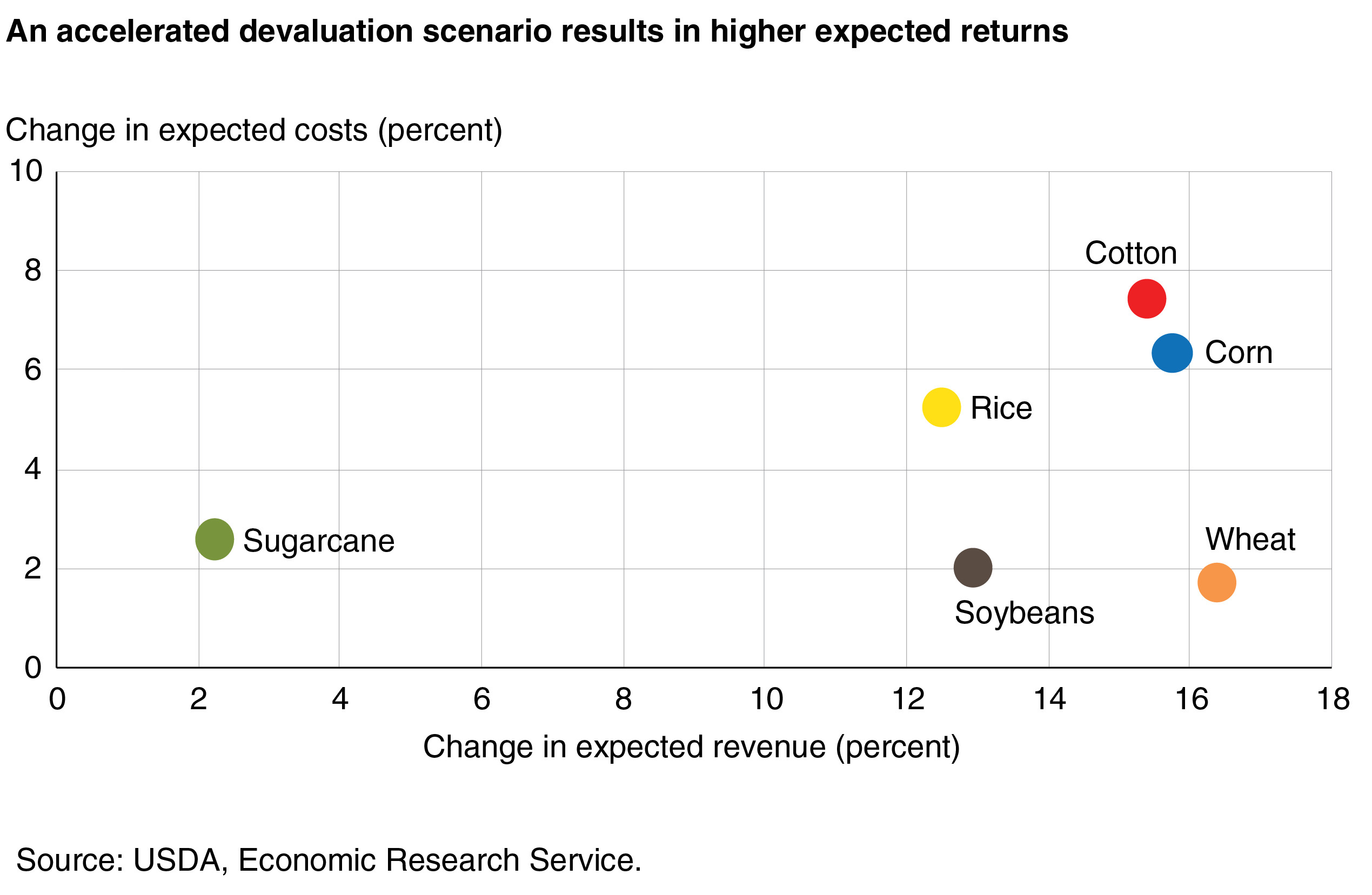

However, currency depreciation also has implications for production costs. Farm inputs like fertilizers and agrochemicals are often imported and priced in dollars. A weaker Real increases the cost of these imported inputs for Brazilian farmers. As illustrated below, commodities like sugarcane, which are heavily reliant on imported inputs, experience a greater cost increase when the Real depreciates, potentially offsetting revenue gains. Conversely, for other commodities, currency devaluation generally leads to a net increase in expected revenue and profitability, making them more attractive for production and export.

A scatter plot that graphs Brazil’s economic returns to commodity production shows in general that as the change in expected costs is higher (y-axis) for a commodity, the change in expected revenue (x-axis) is also higher.

A scatter plot that graphs Brazil’s economic returns to commodity production shows in general that as the change in expected costs is higher (y-axis) for a commodity, the change in expected revenue (x-axis) is also higher.

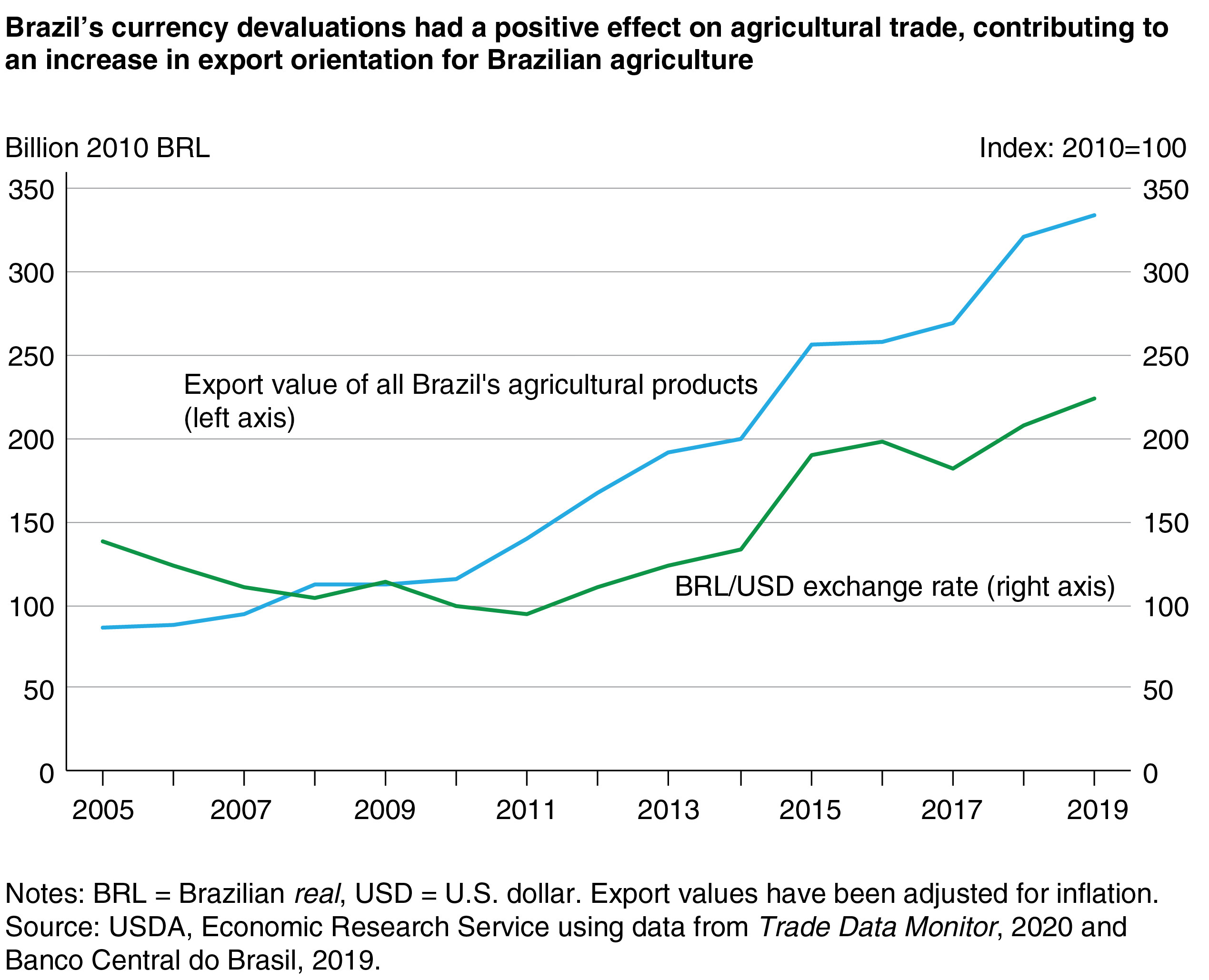

Brazil’s currency devaluations have historically had a positive impact on agricultural trade, contributing to the sector’s increasing export orientation during economic downturns. Total Brazilian merchandise exports grew by a healthy 6.7 percent between 2015 and 2019 following currency devaluations, while overall imports declined, reflecting the domestic economic slowdown. While exports of manufactured goods were less responsive to depreciation during 2011-14 due to weaker global demand, Brazil’s agricultural trade surplus remained robust, even as the non-agricultural trade balance weakened.

A line graph of the Brazilian real/U.S. dollar exchange rate from 2005-19 on falling from 2005-11 then increasing from 2011 onward with the value of Brazilian exports on the left axis increasing incrementally then more steadily from 2011 onward.

A line graph of the Brazilian real/U.S. dollar exchange rate from 2005-19 on falling from 2005-11 then increasing from 2011 onward with the value of Brazilian exports on the left axis increasing incrementally then more steadily from 2011 onward.

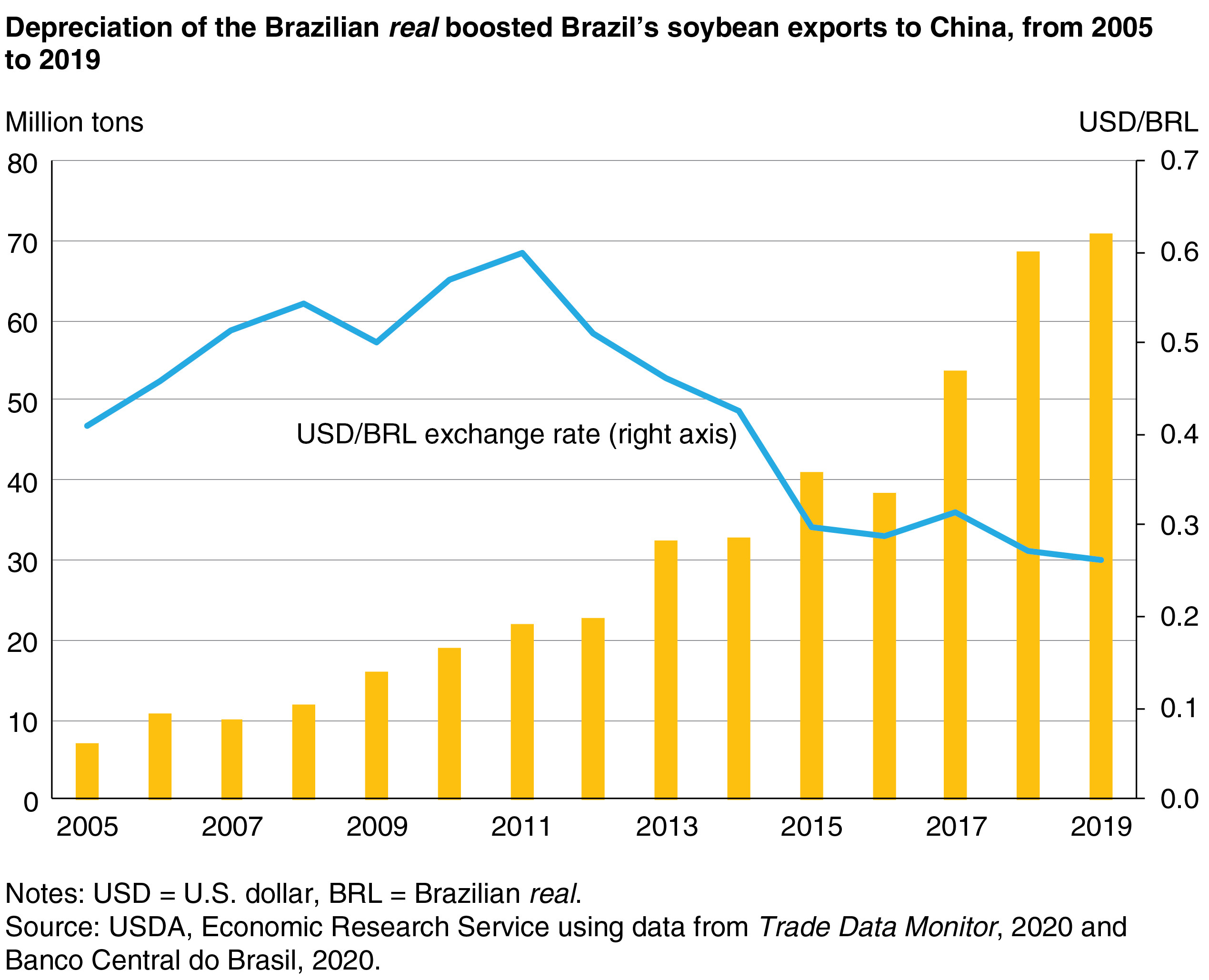

The soybean sector has been a prime beneficiary of currency devaluations. Depreciations of the Real have encouraged farmers to expand soybean planting areas, leading to significant production increases. This surge in production fueled export growth, solidifying Brazil’s position as the world’s leading soybean exporter. Between 2005 and 2019, Brazil’s annual average soybean exports reached 42 million metric tons, alongside 18 million metric tons of corn. China’s escalating demand for soybeans has been a crucial factor driving this growth in Brazilian agricultural exports. This trend is likely to continue, especially if Chinese demand further increases. Brazil’s soybean exports to China surged from 7.2 million metric tons in 2005 to 68.6 million metric tons in 2019, a dramatic increase facilitated by the substantial depreciation of the Real.

A bar graph of Brazil’s soybean exports from 2005-19 increasing slowly but picking up in 2013 as the overlaid line graph of the Brazilian real/U.S. dollar exchange rate indicated depreciation of the real beginning in 2012.

A bar graph of Brazil’s soybean exports from 2005-19 increasing slowly but picking up in 2013 as the overlaid line graph of the Brazilian real/U.S. dollar exchange rate indicated depreciation of the real beginning in 2012.

As favorable exchange rates kept Brazilian commodities competitively priced internationally, China’s growing appetite for Brazilian soybeans and other commodities spurred further growth in agricultural exports after the 2014-16 recession. China has become a major market for a diverse range of Brazilian agricultural products, including soybean meal, corn, sugar, cotton, coffee, and meat. China is Brazil’s top trading partner, accounting for 30 percent of Brazilian exports and 20 percent of imports. Brazilian exports to China received an additional boost when China imposed higher tariffs on U.S. agricultural products in 2018. In contrast, Brazil’s exports to other key markets like the European Union and MERCOSUR declined during this period. Manufactured exports experienced much slower growth, reflecting weaker global demand and the inherent challenges in rapidly restructuring manufacturing production.

Future Scenarios for Brazil Money and Agriculture

Understanding the interplay between economic conditions and Brazilian agriculture is crucial for assessing the prospects for U.S. agricultural exports, given Brazil’s significant and growing presence in global agricultural markets. A recent study by the Economic Research Service (ERS) explored the impact of macroeconomic variables, simulating the effects of policy-driven currency depreciation and sustained macroeconomic growth on Brazil’s future agricultural output and trade.

The USDA’s Agricultural Projections to 2029, released in February 2020, anticipate continued growth in Brazilian agricultural production and exports over the next decade. ERS simulations suggest that this growth could accelerate if the Real depreciates more than currently projected. Conversely, stronger economic growth in Brazil could lead to increased domestic meat consumption and greater domestic utilization of feedstuffs like corn and soybean meal.

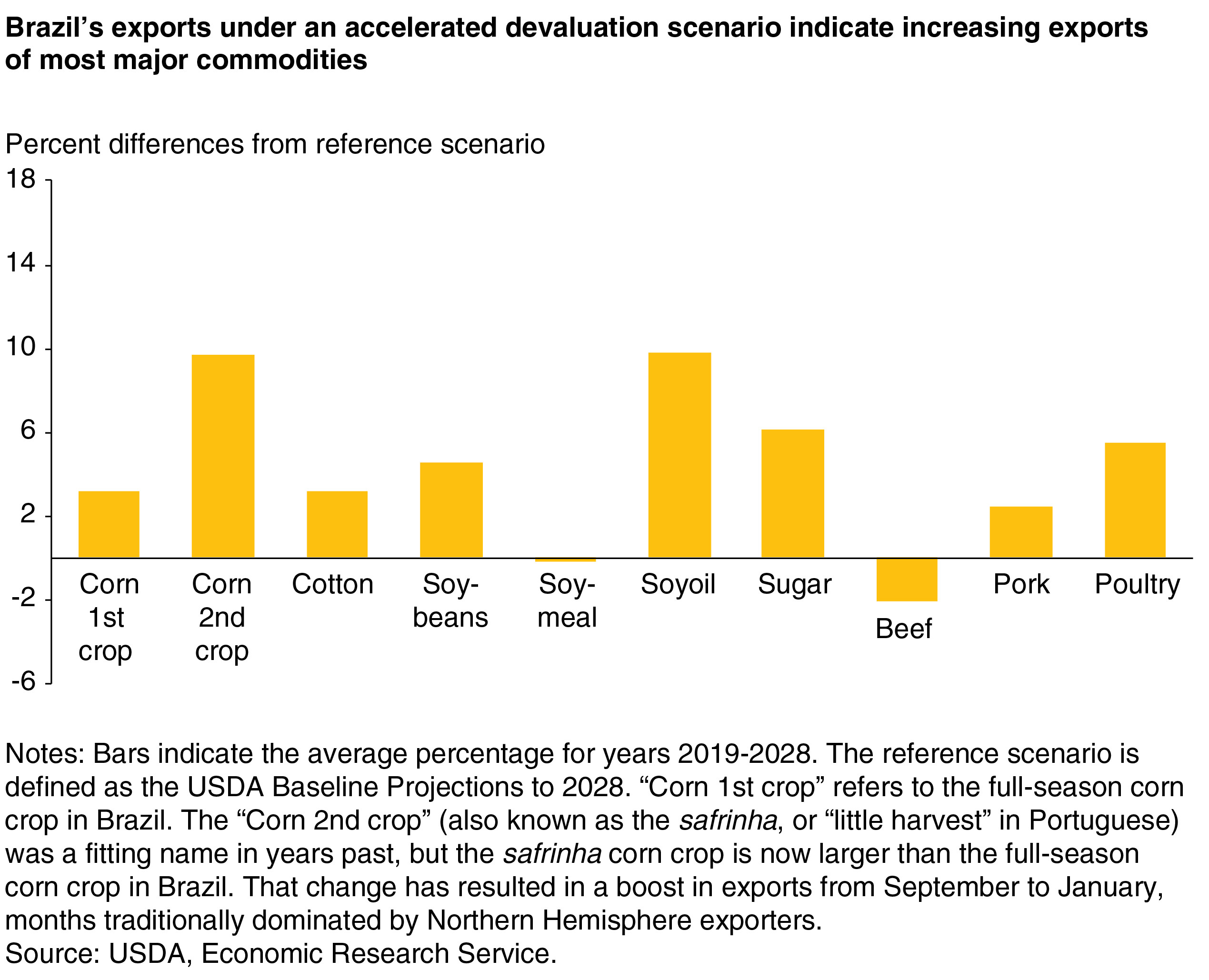

Two simulated macroeconomic scenarios – accelerated currency depreciation and sustained economic growth – are illustrated below. Key findings include:

- Faster depreciation of the Real could drive even faster growth in Brazilian exports than current USDA projections. Simulations indicate that Brazil’s aggregate exports of major commodities could be 5.6 percent higher, and international prices 2.7 percent lower by 2028, compared to USDA’s February 2020 projections.

- Changes in net returns could shift cropland from sugarcane to soybeans and corn. However, reduced fuel imports could increase sugarcane use for ethanol production.

- Faster economic growth in Brazil could reduce beef and pork exports due to increased domestic meat consumption, narrowing the price gap between red meat and chicken. Increased poultry exports, driven by Brazil’s price competitiveness as the world’s largest chicken meat exporter, are expected. More Brazilian corn would be used for animal feed, and soybean processing for livestock feed would increase. Corn exports would decline slightly, while soybean exports would remain largely unchanged.

A bar graph indicating increases up to 10 percent in Brazil’s commodity exports for 2018-28

A bar graph indicating increases up to 10 percent in Brazil’s commodity exports for 2018-28

Change in Brazil’s exports in 2019-28 under accelerated devaluation scenario

| Commodity | Exports in reference scenario, 2019-28 | Accelerated devaluation scenario, 2019-28 |

|---|---|---|

| Million metric tons | Percent change | |

| Beef | 2.5 | -2.1 |

| Corn | 39.5 | 12.9 |

| Cotton | 1.5 | 3.2 |

| Ethanol | 1.3 | -13.7 |

| Pork | 1.0 | 2.4 |

| Poultry | 5.5 | 5.5 |

| Rice | 1.1 | 8.3 |

| Soybeans | 80.2 | 4.5 |

| Sugar | 32.2 | 6.1 |

| Wheat | 0.8 | 3.1 |

| Source: USDA, Economic Research Service research results. |

Increased Competition for US Farmers Due to Brazil Money Policies

Macroeconomic policies, particularly those related to brazil money and currency exchange, have been pivotal in Brazil’s agricultural expansion and its emergence as a significant competitor to the United States in global agricultural markets, even amidst economic recessions.

The combined efforts of Brazilian farmers and supportive government policies during the 2014-16 recession led to increased cropland and enhanced export competitiveness through support programs and transportation infrastructure projects that lowered production and marketing costs. While sustained periods of Real depreciation have boosted export competitiveness, other factors, including declining oil prices, rising biofuel demand, and shifts in macroeconomic conditions in Brazil and competitor nations, have also played a role.

The direction of Brazil’s exchange rate, a key element of brazil money policy, is a significant determinant of its export competitiveness. As Brazil’s influence in international markets grows, U.S. farmers producing competing products may face increased competition, potentially leading to price declines and reduced U.S. commodity exports. ERS research suggests that Brazil still possesses substantial pastureland suitable for agricultural expansion, with further shifts in production patterns and yield improvements expected in the coming years. This will further enhance the sector’s ability to capitalize on growing global demand for feedstuffs.

COVID-19 Impacts and Vulnerabilities Related to Brazil Money

The COVID-19 crisis abruptly halted Brazil’s economic recovery that had been underway from 2017 to 2019. Brazil’s GDP is now projected to decline significantly in 2020, accompanied by a decrease in domestic demand. Major concerns regarding COVID-19’s impact on Brazilian agriculture center on its effects on domestic grain and meat production, the recovery of domestic demand, and international demand for Brazilian commodity exports. The health crisis is threatening per capita income recovery as unemployment rises and economic activity in manufacturing and services sectors contracts due to lockdowns. New Chinese requirements for COVID-19 testing of meat products will increase costs for Brazilian slaughterhouses.

Despite disruptions at domestic and international ports, commercial agriculture has largely remained operational, and export activity in the first half of 2020 was robust, supported by a weaker currency (a 41 percent depreciation of the Real by June 2020 compared to the previous year).

Brazil’s future agricultural export growth remains closely tied to global economic growth. Pre-pandemic USDA projections anticipated long-term global demand growth driving increased demand for Brazilian commodities. With the Brazilian government now providing increased domestic economic incentives to the agricultural sector in response to COVID-19, Brazil is expected to further enhance its agricultural competitiveness over the next decade. However, the pandemic-induced global lockdowns, financial turmoil, and associated recessions present new challenges. The effectiveness of policy measures to revive the economy and further devalue the currency may be diminished by reduced global demand, making the overall economic outlook uncertain.