Have you ever stopped to think about the term “nonprofit” and what it truly implies? Many recognize that nonprofit organizations benefit from tax exemptions, a significant advantage provided by the government. However, the question naturally arises: if these entities are indeed “nonprofit,” how do they sustain their operations and achieve their missions?

Furthermore, it’s common advice to encourage nonprofits to “operate like businesses.” Yet, if the fundamental purpose of a business is to generate profit, what does this guidance really signify for an organization that isn’t driven by profit?

These are crucial questions, especially for those new to the nonprofit sector. Whether you’re considering establishing a nonprofit, working within one, or becoming a donor, understanding the financial mechanisms of these organizations is essential. This guide will serve as an introduction to the world of nonprofits, focusing on the pivotal question: How Do Nonprofits Make Money?

Understanding the “Nonprofit” in Nonprofit Organization

Nonprofits are widely recognized for their commitment to charitable causes, uniting individuals driven by a shared desire to contribute to a greater good. They bring together people who are passionate about working towards a noble purpose.

In contrast to for-profit businesses, where the primary objective is to generate profit for owners and shareholders, nonprofits operate under a different principle. When an organization officially registers as a federally recognized nonprofit with 501(c)(3) status in the US, it commits to reinvesting any surplus revenue back into the organization itself. This reinvestment directly supports its mission and operations. In return for this commitment, the organization receives a crucial benefit: tax-exempt status.

In simpler terms, a nonprofit organization is a collective of individuals united by a common cause and perspective, typically focused on delivering a service to a specific community or the wider world. From an economic standpoint, it’s an entity that utilizes any revenue exceeding its expenses to expand or enhance its services, a practice that is acknowledged and incentivized through tax exemptions.

Why Become a Nonprofit? The Advantages of 501(c)(3) Status

Registering as an official 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization offers numerous advantages, particularly economic benefits, which are compelling reasons for an organization to pursue this status. These benefits include:

- Tax-Exempt Status: This is arguably the most significant benefit, exempting the organization from paying federal and often state income taxes, as well as potentially property and sales taxes. This allows more resources to be directed towards the mission.

- Eligibility for Grants: Nonprofits are uniquely positioned to access funding through private and public grants. Foundations, government agencies, and corporations often prioritize nonprofits for philanthropic investments.

- Organizational Structure as a Separate Legal Entity: Becoming a nonprofit establishes the organization as a legal entity distinct from its founders and members, providing a layer of legal and financial separation.

- Limited Liability Company (LLC) Status Benefits: Nonprofit status often provides liability protection similar to an LLC, shielding founders, board members, employees, and directors from personal responsibility for the organization’s debts and liabilities.

However, beyond these tangible benefits, the primary driving force for most organizations to become nonprofits is the profound desire to engage in meaningful work that positively impacts communities and the world. It’s about prioritizing purpose over profit, and dedicating resources to addressing societal needs.

Key Differences Between For-Profit and Nonprofit Organizations

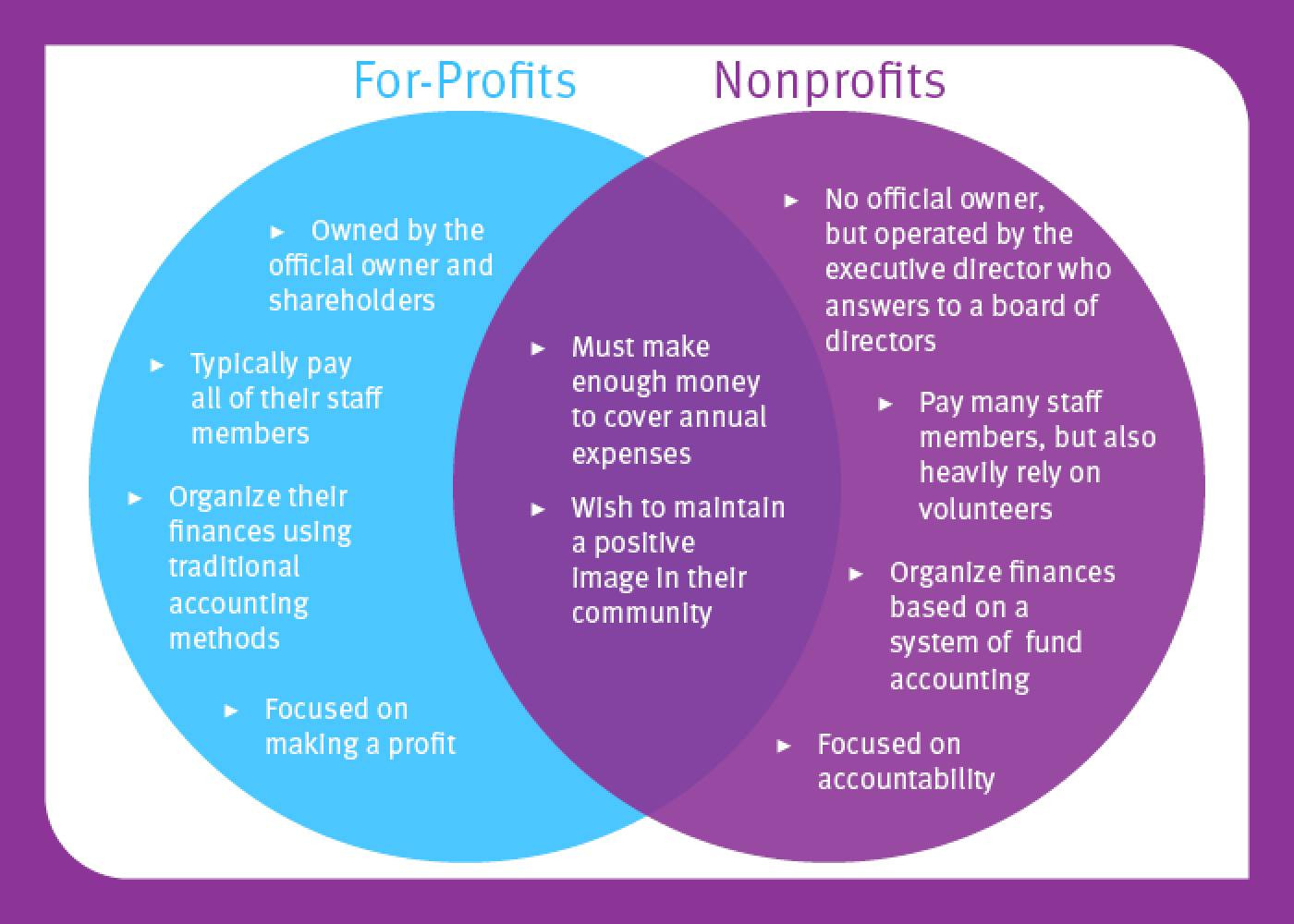

The most fundamental distinction between for-profit and nonprofit organizations lies in their primary motivation: profit. While profit generation is the core objective for businesses, it is explicitly not the driving force behind nonprofits. Beyond this, several other operational and structural differences are crucial to understand.

Venn diagram comparing for-profit to nonprofit

Venn diagram comparing for-profit to nonprofit

For-profit Organizations:

- Ownership Structure: For-profit organizations are owned by individuals, partners, or shareholders. These owners directly benefit from the company’s profits, receiving dividends or increased company value.

- Staff Compensation: Typically, for-profit companies operate with a paid staff across all levels, except for occasional internships. Employee compensation is a direct operational cost factored into profit calculations.

- Financial Accounting: For-profits utilize standard accounting practices focused on profitability. Financial management is geared towards covering expenses, maximizing revenue, and ultimately generating profit for distribution to owners and shareholders.

Nonprofit Organizations:

- Ownership and Governance: Nonprofits do not have individual owners. Instead, they are governed by a volunteer board of directors who oversee the organization’s mission and activities. An executive director or CEO manages day-to-day operations and reports to the board.

- Staff and Volunteers: Nonprofits often employ paid staff, but they also heavily rely on volunteers to carry out their mission and manage operations efficiently, often within constrained budgets. Volunteers are a critical resource, extending the reach and capacity of the organization.

- Fund Accounting: Nonprofits employ a specialized system called fund accounting. This method is designed to track and manage restricted funds (donations or grants earmarked for specific purposes) separately from unrestricted funds, ensuring financial transparency and compliance with donor intent and grant requirements.

Despite these differences, both types of organizations share some common ground. Both nonprofits and for-profits need to generate sufficient revenue to cover expenses and maintain financial stability. Furthermore, both are concerned with public perception and strive to maintain a positive image to attract support, whether it’s customers for for-profits or donors and volunteers for nonprofits.

Exploring the Diverse Revenue Streams of Nonprofits

It’s clear that nonprofits, just like any other functional organization, require a steady flow of money to operate effectively. They incur costs for essential resources such as office space, staff salaries, necessary equipment, marketing and outreach, and the routine expenses of daily operations. Crucially, funds are also needed to directly deliver the programs and services that fulfill their mission. Therefore, understanding how nonprofits make money is paramount to appreciating their sustainability and impact.

However, due to their tax-exempt status, there are specific guidelines and sometimes restrictions on how nonprofits can generate income. Traditional fundraising activities, such as direct donations, revenue from fundraising events, and sales of items explicitly for fundraising purposes, are generally permissible and common. While other income-generating activities might be acceptable, they must be carefully managed to avoid jeopardizing the organization’s tax-exempt status. For instance, selling donated goods is usually acceptable, but engaging in unrelated business ventures on a large scale could raise concerns.

Let’s examine the primary sources of revenue that sustain nonprofit organizations in more detail.

Nonprofit funding sources

Nonprofit funding sources

Earned Income: Mission-Aligned Revenue Generation

While many people associate nonprofits primarily with donations and fundraising, earned income is a vital and often substantial revenue stream for many of these organizations. Earned income refers to funds that nonprofits generate themselves through their activities, rather than relying solely on philanthropic contributions. This self-generated revenue plays a critical role in diversifying their funding base and enhancing their financial stability.

To maintain 501(c)(3) status, it is crucial that this earned revenue is directly linked to the organization’s mission. The IRS scrutinizes unrelated business income (UBIT), which is income from a trade or business regularly carried on by a nonprofit that is not substantially related to its exempt purpose. UBIT is taxable and can potentially jeopardize tax-exempt status if it becomes a primary activity.

Earned income can manifest in various forms, depending on the nonprofit’s mission and activities. Some common examples include:

- Sales of Merchandise: Nonprofits often sell mission-related merchandise. This could include branded apparel, books, educational materials, artwork created by beneficiaries, or products that directly support their cause, like fair-trade goods for an organization promoting economic development. For example, a museum might sell exhibition catalogs and educational toys, or an environmental group could sell reusable water bottles and organic cotton t-shirts.

- Fees Charged for Services: Many nonprofits provide services for a fee. This can range from program fees for educational workshops or training, to charges for counseling services, healthcare clinics, or legal aid. Cultural organizations may charge admission fees for events or performances. Service fees directly contribute to covering the costs of delivering these mission-aligned programs. A youth development organization might charge a fee for after-school programs, while a professional association could charge membership dues that cover the cost of professional development and networking events.

- Membership Fees: Membership models provide a recurring revenue stream and build a sense of community around a nonprofit’s mission. Membership fees can offer various benefits to members, such as discounted services, exclusive content, voting rights (in membership organizations), or recognition. Museums, public radio stations, and advocacy groups often rely on membership programs.

- Renting Out Physical Space: Nonprofits that own facilities may generate income by renting out space when it’s not being used for their primary activities. This could include renting out meeting rooms, event spaces, classrooms, or even office space to other organizations or individuals. Community centers, churches, and arts organizations often utilize this strategy.

It is crucial for nonprofits to carefully assess the relevance of any earned revenue streams to their core mission. If there’s any uncertainty about whether an income-generating activity is sufficiently related to the nonprofit’s exempt purpose, it is always prudent to consult with a nonprofit accountant. An expert can provide guidance on whether the income is mission-aligned and how to properly report it to ensure compliance with tax regulations.

Individual Contributions: The Power of Philanthropy

Individual contributions represent the cornerstone of funding for many nonprofit organizations. These are donations made directly by individuals – from grassroots supporters giving small amounts to major donors making transformational gifts. Cultivating and nurturing relationships with individual donors is a critical function for most nonprofits.

Individual donations vary significantly in size, form, and method of giving. Understanding the different types of individual contributions is essential for effective fundraising and donor relations:

- Event Contributions: Fundraising events are a common avenue for individual giving. Donations made during event registration or directly at fundraising events (galas, auctions, walks, runs, etc.) are categorized as individual contributions. These events not only raise funds but also provide opportunities for community engagement and donor cultivation.

- Online Donations: With the rise of digital giving, online donations have become increasingly significant. Gifts received through a nonprofit’s website donation page, online fundraising platforms, or social media campaigns collectively contribute a substantial portion of individual donations. Online giving is convenient and accessible, broadening the potential donor base.

- Stock Donations: Donating appreciated stock holdings offers tax advantages to donors and can be a significant source of funding for nonprofits. Donors may choose to contribute stocks rather than cash, especially if they have held appreciated securities for more than a year. These donations are often facilitated through donor-advised funds, which allow donors to manage their charitable giving more strategically.

- Planned Gifts: Planned gifts are commitments made by donors to provide a gift to a nonprofit at a future date, often as part of their estate planning. These gifts commonly take the form of bequests in wills, charitable trusts, or charitable gift annuities. Planned gifts often represent the largest individual donations a nonprofit receives and contribute significantly to long-term financial sustainability.

- In-Kind Contributions: In-kind donations are gifts of goods or services rather than cash. Examples include donated office supplies, furniture, professional services (legal, marketing, etc.), or donated goods for programs (food, clothing, etc.). While not cash, in-kind donations have real value and must be properly recorded in the nonprofit’s accounting system. Accurately valuing and acknowledging in-kind donations is crucial for both financial reporting and donor recognition.

Nonprofits invest considerable effort in acquiring and retaining individual donors. Donor retention is paramount because it is generally more cost-effective to cultivate existing donors than to constantly acquire new ones. Nonprofits implement various strategies to steward individual donors, fostering deeper engagement with the mission, providing regular updates on impact, and recognizing their contributions. Building strong relationships with individual supporters is essential for ensuring a sustainable and growing base of philanthropic support.

Grants: Securing Funding from Foundations and Institutions

Grant funding represents another critical revenue stream for nonprofits, particularly for specific projects or programs. Grants are typically awarded by grant-making organizations – foundations, government agencies, corporations, or other nonprofits – to support initiatives that align with their philanthropic priorities.

Grant-makers carefully evaluate applications to ensure that their funding is directed toward impactful projects with achievable goals and that the applicant nonprofit’s mission and values are compatible with the grant-maker’s own. Therefore, the grant proposal process is often competitive and requires nonprofits to present a compelling case for funding.

Organizations that offer grants to nonprofits are diverse and include:

- Government Entities: Federal, state, and local government agencies offer grants to nonprofits addressing public needs in areas such as health, education, social services, arts, and environmental protection. Government grants can be a significant source of funding, but they often come with specific compliance requirements and reporting obligations.

- Public Charities: Large public charities sometimes operate grant-making programs, re-granting funds they have raised to smaller nonprofits working in related fields. This can be a way for larger organizations to amplify their impact and support grassroots initiatives.

- Community Foundations: Community foundations are place-based grant-makers focusing on addressing needs and opportunities within a specific geographic area (city, region, or state). They pool donations from local individuals and families to support local nonprofits.

- Family Foundations: Family foundations are established by families to manage their philanthropic giving. They often reflect the family’s values and interests and may focus on specific causes or geographic areas.

- Private Foundations: Private foundations are typically funded by an individual, family, or corporation. They operate independently and have their own grant-making priorities, which can range across diverse fields.

A critical aspect of grant seeking is meticulously adhering to the grant application guidelines provided by each grantor. Grant-makers typically have specific formats, deadlines, and required information for proposals. Nonprofits must carefully review these guidelines and tailor their proposals to meet the specific criteria and demonstrate a strong alignment with the grantor’s mission and funding priorities. A well-crafted grant proposal articulates the project’s need, methodology, expected outcomes, and the nonprofit’s capacity to successfully implement the project.

Managing grant funding effectively presents unique financial challenges for nonprofits. Grant funds are frequently restricted, meaning they can only be used for the specific project or purpose for which they were awarded. This requires nonprofits to implement robust financial tracking systems to segregate grant funds and ensure they are used solely for the intended purposes. Fund accounting is particularly crucial for managing restricted grant funds.

Furthermore, grant-makers require regular reporting on how grant funds have been spent and the progress made towards project goals. Nonprofits must establish effective grant management systems to track deadlines for reporting, collect necessary data, and prepare timely and accurate reports for grant-makers. Strong grant management is essential for maintaining accountability and building positive relationships with grant-making organizations, which can lead to future funding opportunities.

Investments: Growing Assets and Long-Term Sustainability

While less commonly considered a primary revenue source, investments can play a strategic role in a nonprofit’s financial sustainability. Nonprofits can utilize investment strategies to grow their assets over time, build reserve funds for future needs, and potentially generate a stream of investment income.

Nonprofits, like individuals and businesses, can open brokerage accounts and invest in various financial instruments, such as stocks, bonds, and mutual funds. Interestingly, their tax-exempt status offers a significant advantage in investing: nonprofits generally do not have to pay income tax on dividends and capital gains earned within their investment portfolios.

Nonprofits typically do not rely on investment income as their main source of operating revenue. Instead, investment activities are often geared towards long-term asset building and strengthening their financial reserves. Building reserves is crucial for weathering economic downturns, addressing unexpected expenses, or funding future strategic initiatives.

The most common form of investment for nonprofits is an endowment. An endowment is a dedicated fund where the principal amount is typically meant to be preserved in perpetuity, while the investment income generated from the endowment is used to support the nonprofit’s mission. Endowments are often established through major gifts from donors, and the terms of the gift may restrict how the endowment income can be used. Endowment income can provide a predictable and sustainable source of funding over the long term, contributing to the financial stability of the organization.

Strategic investment management, including endowment management, requires careful planning, professional expertise, and adherence to responsible investment policies. Nonprofits often work with financial advisors to develop investment strategies that align with their risk tolerance, time horizon, and financial goals. Responsible investment practices ensure that the nonprofit’s assets are managed prudently and ethically, furthering their long-term financial health and mission impact.

Maintaining 501(c)(3) Status: Compliance and Accountability

When an organization registers as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, it enters into an agreement with the federal government. In exchange for tax-exempt status and the associated benefits of being a nonprofit, the organization commits to operating in accordance with specific regulations and using its resources to serve the public good, rather than private interests. Essentially, nonprofits agree to reinvest any surplus revenue back into their mission and operations.

The federal government, through the IRS, has established requirements to ensure that nonprofits uphold this agreement, maintain public trust, and do not abuse their tax-exempt privileges. To maintain 501(c)(3) status, nonprofits must consistently adhere to the following key compliance actions:

- Annual Tax Return Filing: Nonprofits are required to file an annual information return with the IRS, typically Form 990, 990-EZ, or 990-N, depending on their gross receipts and assets. This return provides transparency to the public and the IRS, reporting on the organization’s income, expenses, activities, and governance.

- Donor Acknowledgements: For all individual donations of $250 or more, nonprofits must provide donors with a written acknowledgement (receipt) that meets IRS requirements. This receipt substantiates the donor’s charitable contribution for tax deduction purposes.

- Contractor and Compensation Management: Nonprofits must establish and maintain formal processes for managing contracts and compensation arrangements with both external contractors and internal employees. These processes should ensure that compensation is reasonable and in line with fair market value, avoiding private benefit and ensuring that all arrangements serve the public interest. Many nonprofits have compensation policies to guide salary decisions, particularly for executives.

- Lobbying Restrictions: While nonprofits can engage in some lobbying activities to advocate for their mission, there are limitations on the extent and nature of lobbying they can undertake without jeopardizing their tax-exempt status. Understanding and adhering to these lobbying rules is crucial.

- Political Campaign Activity Avoidance: 501(c)(3) organizations are strictly prohibited from engaging in partisan political campaign activity. This means they cannot endorse or oppose candidates for public office. Even seemingly minor activities, such as providing mailing lists to political campaigns or using organizational resources for political advertising, can violate this prohibition.

- Unrelated Business Income Tax (UBIT) Compliance: As mentioned earlier, income from activities that are not substantially related to a nonprofit’s exempt purpose may be considered unrelated business income and is subject to taxation (UBIT). Nonprofits must identify and properly report UBIT to maintain compliance.

- Seeking Expert Legal and Accounting Advice: Navigating the complex regulatory landscape for nonprofits requires expertise. It is essential for nonprofits to consult with lawyers and nonprofit accountants to ensure they are in compliance with all applicable laws and regulations. Asking the right questions and seeking professional guidance proactively can prevent compliance issues.

The consequences of losing 501(c)(3) status can be severe. If an organization’s tax-exempt status is revoked, it would become liable for paying taxes on all contributions it receives, significantly reducing its financial resources. Furthermore, regaining 501(c)(3) status requires re-application and payment of fees, creating additional administrative and financial burdens. Therefore, prioritizing compliance is paramount for the long-term sustainability and effectiveness of nonprofit organizations.

Budgeting and Financial Management in Nonprofits

Just like for-profit businesses, sound financial management is essential for nonprofit organizations. Budgeting is a fundamental tool for nonprofits to plan their finances, allocate resources effectively, and ensure they are operating sustainably.

Nonprofit budgeting involves creating a comprehensive financial plan that considers anticipated revenue from all sources (donations, grants, earned income, etc.), projected expenses across all programs and administrative functions, and any restrictions on funding (e.g., grant restrictions). The budget serves as a roadmap for the organization’s financial activities throughout the year. Nonprofits strive to adhere to their budgets, monitoring actual performance against planned targets and making adjustments as needed.

In addition to annual budgets, nonprofits utilize key financial statements to manage their finances and assess their financial health. These statements provide critical insights into the organization’s financial position and performance:

- Statement of Activities (Income Statement): This statement, analogous to an income statement in for-profits, reports the nonprofit’s revenues and expenses over a period of time (typically a year). It shows how the organization’s net assets have changed due to operating activities.

- Statement of Financial Position (Balance Sheet): Similar to a balance sheet for for-profits, this statement presents a snapshot of the nonprofit’s assets, liabilities, and net assets (equity) at a specific point in time. It reflects the organization’s financial resources and obligations.

- Statement of Cash Flows: This statement tracks the movement of cash both into and out of the organization over a period. It categorizes cash flows into operating, investing, and financing activities, providing a clear picture of how the nonprofit generates and uses cash.

Any surplus revenue that a nonprofit generates – revenue exceeding expenses – is not distributed as profit. Instead, it is reinvested back into the nonprofit’s mission, programs, and operations. Surplus funds may be used to expand programs, improve services, invest in infrastructure, or build a reserve fund. Reserve funds are crucial for providing a financial cushion to address unexpected challenges, seize new opportunities, or ensure continuity during periods of economic uncertainty. Sound financial management, including budgeting and the use of financial statements, is essential for nonprofits to operate effectively, achieve their missions, and maintain public trust.

Staff Compensation in Nonprofits: Balancing Mission and Fair Pay

We have explored extensively how nonprofits generate revenue and manage their finances at the organizational level. But what about the individuals who work for nonprofits – the staff members and founders? Unlike for-profit companies where owners and shareholders benefit directly from profits, nonprofits operate under a different model.

It’s important to understand that nonprofit organizations have founders, not owners. These founders cannot personally benefit from the net earnings of the organization. However, this does not mean that individuals working for nonprofits cannot be compensated. Nonprofits can and do pay salaries to their staff, including executive leadership and founders who work for the organization. The key principle is that any financial surplus generated by the nonprofit is reinvested in the mission, not distributed to individuals for private gain. Nonprofits strive to achieve positive revenue to ensure financial stability, fund future operations, and build reserves, but profit is never distributed to individuals or private interests.

Many nonprofits implement a formal compensation policy to guide decisions about staff salaries, particularly for executive positions. These policies often outline a process for researching and benchmarking salaries against comparable positions in similar organizations (both nonprofit and for-profit) to ensure that compensation is reasonable and competitive. Transparency in compensation practices is important for maintaining trust and accountability.

Beyond competitive salaries, nonprofits often focus on offering a comprehensive compensation package to attract and retain talented staff. This includes benefits that go beyond just the monthly paycheck. Nonprofits often offer incentives such as:

- Increased Flexibility: Nonprofits are often more flexible in accommodating staff needs related to work schedules, remote work options, and work-life balance. This flexibility can be a significant attraction for employees.

- Enhanced Benefits: In addition to standard benefits like medical and dental insurance, life insurance, and retirement plans, nonprofits may offer enhanced benefits packages. These could include opportunities for professional development, sabbaticals, tuition reimbursement for further education, generous vacation time, or robust parental leave policies.

- Purposeful Work: For many individuals, the primary motivation for working in the nonprofit sector is the opportunity to engage in meaningful work that makes a positive difference in the world. The intrinsic reward of contributing to a cause they believe in is a powerful motivator.

- Positive Community Culture: Nonprofits often cultivate a strong sense of community and shared purpose among their staff. Employees often value working in environments where they feel respected, valued, and connected to a mission that resonates with them. A positive and supportive organizational culture can be a significant factor in employee satisfaction and retention.

While nonprofits do not distribute profits to individuals, they recognize the importance of attracting and retaining qualified staff to achieve their missions effectively. Offering competitive salaries and comprehensive benefits, coupled with the inherent rewards of mission-driven work, enables nonprofits to build strong teams and ensure organizational success. Staff retention is particularly crucial for nonprofit financial stability, as the costs associated with employee turnover and recruitment can be significant.

The Bottom Line

Nonprofits operate under a fundamentally different financial paradigm than for-profit companies. They are not driven by the pursuit of profit for owners or shareholders. Instead, their financial goal is to achieve sustainability – to generate sufficient revenue to cover their operating expenses, deliver their programs and services, build reserves for future needs, and fairly compensate their employees. While profit maximization is not the objective, financial viability is essential for nonprofits to fulfill their missions effectively and make a lasting impact. They require capital to operate, and they strategically cultivate diverse revenue streams through fundraising, earned income, grants, and investments to ensure their long-term sustainability and continued service to the community.

To delve deeper into developing a sustainable financial model for your nonprofit or to discuss your organization’s specific financial situation, we encourage you to contact a nonprofit accountant. Expert financial guidance is invaluable for navigating the complexities of nonprofit finance and ensuring long-term organizational health.

If you are interested in expanding your knowledge of nonprofit funding and financial management, we recommend exploring these additional resources:

Learn more about how nonprofits make and allocate money.