You’ve undoubtedly heard the distinctive keyboard riffs of Money Mark. That iconic opening to Beck’s “Where It’s At”? That’s Money Mark. The eclectic and engaging soundtrack of Netflix’s Ugly Delicious? Again, Money Mark. And then there’s his foundational work with the Beastie Boys, a collaboration that began with their groundbreaking 1992 album, Check Your Head. As Mike D. of the Beastie Boys keenly observed in The Beastie Boys Book, Money Mark, whose full name is Mark Ramos Nishita, brought a level of musicality and sophistication that elevated their sound.

“Mark was the best musician of the four of us,” Mike D. wrote. “We’d never played with a piano player before, and something about that instrument made things sound a little more like real music. And when he broke out his clavinet, he was on some Stevie Wonder shit. Also, Mark is the only one of us who could actually sing a song without sounding like a toddler.”

Born in Detroit and raised in Gardena, California, Money Mark operates from his studio near the Beastie Boys’ old G-Son Studios in Atwater Village. His career is a testament to versatility and enduring relevance in the music industry. Beyond his core collaborations, he’s lent his talents to a diverse roster of artists, including Femi Kuti, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Yoko Ono, and De La Soul. His compositions extend beyond Ugly Delicious to include scores for the documentary Beautiful Losers and performances on Yo Gabba Gabba!. Adding to his impressive portfolio, Money Mark has also released several acclaimed solo albums, showcasing his unique musical vision and financial independence as an artist.

In a recent interview, Money Mark discussed his then-upcoming tour with Molotov and a unique two-show engagement with Alexis Taylor of Hot Chip at The Met Cloisters. For the latter, he showcased his invention, the Echolodeon, a “portable electronic/pneumatic musical interface” utilizing repurposed player piano rolls. His creative endeavors also extend to guest appearances on podcasts like Aimee Mann and Ted Leo’s The Art of Process and ongoing work on a screenplay and a new solo album. Furthermore, he was slated to perform at Moogfest 2019 in Durham. This prolific output across various mediums – musician, composer, producer, vocalist, collaborator, inventor, and even carpenter – underscores a career built on diverse skills and smart financial decisions.

The conversation began, perhaps unexpectedly, with tacos, offering a glimpse into Money Mark’s grounded personality and practical approach to life and, by extension, his career.

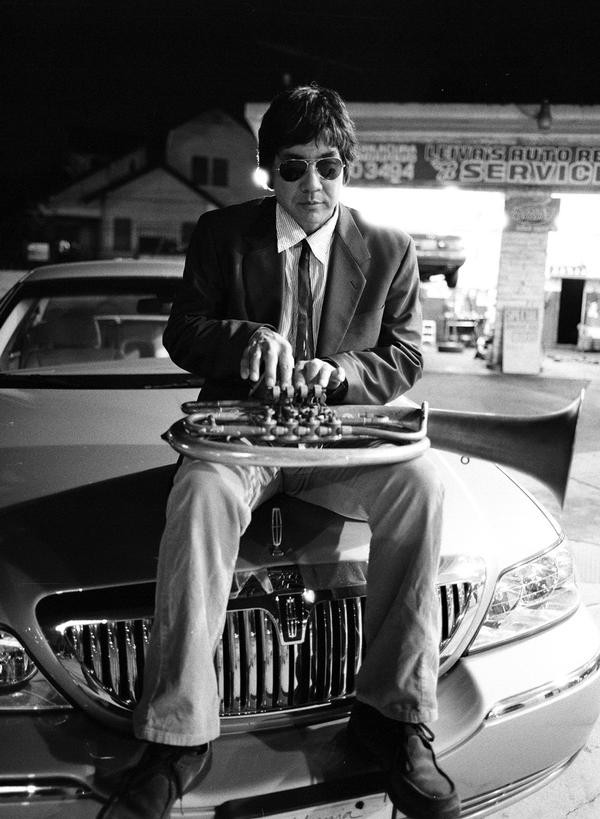

Money Mark in his recording studio, photo credit Autumn de Wilde

Money Mark in his recording studio, photo credit Autumn de Wilde

Money Mark in his recording studio, showcasing his workspace where musical and financial decisions intertwine, photo by Autumn de Wilde.

LT: What’s your favorite taco?

MM: The quick answer is: My recording studio is near Salazar. I think Jonathan Gold put it in his top 101, rest in peace. I’m there once a week, only because I’m next to it. My clients come to my studio and work, and we end up going there.

Their tortillas are great.

The flour tortillas are amazing. It’s got that Asian-y, gumminess to it. Maybe that’s why I like it. It’s like eating an egg roll or something. He really packs the meat on top of it. I take half of it off, and then I can roll it up and eat it like that. But, yeah, it’s a lot of carne.

Here’s my version of the taco. It’s actually the best taco ever.

Those are fighting words, you know.

I’m just kidding!

It’s a special recipe. I’m not going to say where the original is from. So, the masa, right? I go to La Gloria in East L.A. That’s where I get masa. Now, if you’re making a tamale, the masa’s actually different—it has more saturated fat in it. But the tortilla for the taco doesn’t have as much. So, in my version, there are sesame seeds in the masa. Black sesame seeds. And then, when you’re making the taco, supposedly, you roll it in a little ball and then you smash it and it becomes what shape: round? But then when you’re filling it up and folding it, everything falls out the side. Growing up here, I think you could make a burrito out of a lavash, and I’m more a lavash type, so, my taco is a square taco. Square corn tortillas!

Have you lived in LA most of your life?

Yes. I grew up in Gardena, and my parents felt comfortable in Gardena because it was ethnically mixed, multicultural. My mother’s Mexican American, born in San Antonio, Texas, and my father’s Japanese American, born in Hawaii. And there were a lot of Japanese, Hawaiian Japanese in Gardena. My father’s friend was there, and he said, Hey, there’s a place you can rent next to my house.

So we rented that place and had parties on the weekends, played Hawaiian music. My dad’s friend had a Santa Rosa plum tree in his backyard, and at any moment, you could just grab a plum. So on my way to school – school was about 4 blocks away – I would purposefully miss breakfast, because I knew I could just grab a plum, or guava, or a fig, or a grapefruit, an orange. I mean, gosh. They were everywhere. There were empty fields in Los Angeles and that kind of defined Los Angeles for a lot of Angelenos. The empty lot was a playground, and you could cut through them. All the neighborhoods were connected through these empty lots. So kids played in the empty lots: baseball, dirt bike tracks, and then there were fruit trees. Everywhere. It was gorgeous.

From Carpentry to Composition: Building a Sustainable Career

Money Mark’s journey wasn’t a direct path to musical stardom. Prior to becoming a full-time musician, he honed his skills as a carpenter. This background in a skilled trade provided not just a means of income but also instilled a practical, hands-on approach that arguably influenced his multifaceted career in music. He even worked on the set of Pee-wee’s Playhouse, building props and sets, a testament to his diverse talents and willingness to apply his skills across different creative fields. This adaptability is a crucial financial lesson for any creative professional – diversifying skills to ensure consistent income streams.

LT: How did you get involved doing the music for Ugly Delicious?

I was friends with Eric Nakamura, creator, curator of Giant Robot. He introduced me to David Choe, and David Choe introduced me to David Chang, so there you go: Went from Nakamura to Choe to Chang. And I’m Ramos Nishita.

I scored eight episodes, and I was asked to do it by David. It was fun, it was a bit challenging. Eddie Schmidt: amazing producer. The whole crew’s award winners. If you haven’t seen it, I would suggest you do that. It’s about food but not just about food. With David Chang, it’s never just about food. Like with [Anthony] Bourdain, it’s never just about food.

A couple of your songs from Push the Button are in the first few episodes.

Oh, yeah, they used a lot of my back catalog. It seemed to work well. I wasn’t against it, and I would be the first one to say, “Hey this is a forced fit,” or “This is not working.”

I don’t want it to be a business thing. I just want it to work. They were very careful. Good team of creators right there.

Collaboration and Ego: A Daoist Approach to Music and Money

Money Mark’s collaborative spirit is evident throughout his career. He describes his approach as “Daoist,” emphasizing empathy and allowing creativity to flow organically. This philosophy extends beyond music and offers a valuable perspective on financial collaborations and partnerships. Ego, he notes, can be a significant obstacle, particularly in financial negotiations and creative projects. His willingness to prioritize the project’s needs over personal ego has likely contributed to his long-lasting and fruitful collaborations.

You do a lot of collaborations, and you do your own work as well. Do you have different mentality when you’re working by yourself versus with other people?

It’s an ego check. I have a technique that I use. I’m not sure how to describe it. It’s kind of Daoist, actually: You walk into a space with kind of an immense empathy, and you just let things start to happen. And then you fit in where you can. It’s that simple. I think people’s ego – my ego, too – gets in the way, or it can. When I was first starting out, yeah, I wanted my voice on this thing, I wanted it to be loud. That’s just not the way to do it anymore, really, for me. And maybe there are gigs where they’re like, “Hey, you’re not really asserting yourself in this.” It’s my decision to say, “I don’t think my voice is right for this thing and I’m going to go with it and see what happens,” or “Well, let me plug in my keyboard right now and try.”

Sometimes there’s a starting point already. When you’re working on a TV show, they have temp music, so I always say, “Send me the scene without the music, then send it to me with the music.” Then I’ll make some music for it, then listen to the other one. And I should say it’s not just music, because nowadays, it’s sound design. Sound design and music are kind of becoming into one thing. It’s a different beast. You’re trying to tell a story, someone else’s story. When you’re trying to tell someone else’s story, you hold yourself back, until you’ve fully internalized the thing. It’s a little tricky. It could be the shortest scene that you’re watching over and over and over, watching the bookends, to see where it came from and where it’s going.

In the end, sometimes no music is perfect.

Theater, Technology, and the Roots of Innovation

Money Mark’s background in theater is another key element in understanding his diverse skillset. He studied all aspects of theater, from acting to set design, gaining a holistic understanding of creative production. Coupled with his father’s influence as an electronics engineer, this theatrical foundation shaped him into an “electronic musician” with a deep appreciation for both the artistic and technical sides of music creation. This blend of artistic and technical knowledge is increasingly valuable in today’s music industry and the broader digital landscape, where innovation and adaptability are financially rewarded.

You were a carpenter before you got into music professionally, right?

From way back, way back, my mother’s family are musicians and my father was an electronic engineer. He worked for Howard Hughes, the Hughes Aircraft Company. And I became an electronic musician. Then I studied traditional songwriting and I got into building songs, and then I figured out how they made those songs, and then I figured out how they use the machines and my father showed me how to use all the electronic stuff. I’m a product of their design. With all that interest, I got interested in theater. I studied theater in school.

Like sound and sets?

No, no, I was acting. Everything. I think when you study theater, you know everything. Because you’re creating worlds and you see shadows and the light and you see colors and the whole creation. And because of that, I could morph into a set carpenter or a musician or a songwriter. I could do anything. Well, it felt like it. It was really cool.

When I was working in the theater, there were no Asians. That’s why I worked as a musician.

Oh, really?

Yeah, because I couldn’t get a role. I was going to be gang member, or robber or a thief, something like that. Bit part, like driving a cab or something. I was like, Nah, that’s not what I was trained to do, and I don’t want to do that.

I read somewhere that you were working as a musician while also working as a carpenter on the set of Pee-wee’s Playhouse?

Well, I was working on the Hollywood Center Studios Lot. I was so happy to work on that lot because that was Francis Ford Coppola’s lot, and I was a big fan of his movie One from the Heart and the score, which is amazing. I loved those songs and I loved the movie. So, it was a dream to walk on to that lot. And Paul Reubens’s show was on that lot, so whenever the main art director needed someone, they would just call us and we’d do it really quick. I was good at working fast, with a high quality, so I got a lot of jobs making stuff for Pee-wee’s Playhouse.

The first thing I made was a baby bassinet. I don’t know why. There were some miniatures I made, too.

Money Mark and David Byrne backstage at the Greek Theatre, photo credit Jesse Lirola

Money Mark and David Byrne backstage at the Greek Theatre, photo credit Jesse Lirola

Money Mark and David Byrne backstage, highlighting collaborations and networking as key financial strategies in the music industry, photo by Jesse Lirola.

Mentorship and Mastery: Lessons from Robert Fripp

A pivotal moment in Money Mark’s musical development was his participation in Robert Fripp’s Crafty Guitar retreat. This experience, focused not just on music but also on disciplines like meditation and even cooking, highlights the importance of holistic development for sustained creative and financial success. Learning from established masters and embracing diverse influences can provide invaluable insights applicable to both artistic and financial growth.

And you were in bands and playing music during this time?

Yeah. Right around that same time — this was long before the Internet — I was really interested in Robert Fripp’s Crafty Guitar thing that was happening. And I wrote a letter to Robert Fripp, and he answered my letter. And in the letter, he said, I will invite you to the next time we do the Crafty Guitars retreat.

One happened to be coming up in Malibu. He asked me to buy this special Takamine guitar, and I did. I attended. The first day, the instruction from him was to meet the next morning at 6 am in his room. And when I got to the room, I was the first one. He was sitting in a chair, and there were some other chairs around, and he was sitting in the center of the room. Sitting there. Eyes closed. And I realized, Oh, he’s meditating.

So I meditated with Robert Fripp. After the meditation session, he kind of woke up, said, Good morning, we’re going to now walk to the commissary.

We walked across this field to a small cafeteria-type place and walked into the kitchen area. And there were fruits and vegetables, and we made soup and we made bread.

Oh, so this was a different sort of music retreat.

I learned a lot. It changed my life, actually. He was using The Moosewood Cookbook. I use it to this day. I see recipes embedded into my brain. It was amazing. I learned a little bit about music.

After that experience, I decided I have to be all in [with music]. I had a lot of skills by that time, so it was easy for me to be all in. To survive in the world, you really have to have skills. Like, if that’s not going to work out for you, you need to be able to do something else. Fortunately, things happened and I just stayed a musician, then turned into a composer. And I’m still doing it.

Going “All In” with Calculated Risk

Money Mark emphasizes the importance of having a “backup” plan, a set of skills to fall back on. However, he also recognizes the necessity of going “all in” when pursuing a creative passion. This isn’t about reckless abandon but rather calculated risk-taking based on a solid foundation of skills and experience. His journey illustrates that financial security and creative fulfillment aren’t mutually exclusive but can be achieved through strategic career management.

I think that’s hard for a lot of creative people, to decide at what point they should go all in on their creative thing.

You have to have something there to back it up. It is true. I just read Originals by Adam Grant, and everyone in that book who soared to the top of their field all had something. The perception is you have to risk everything and you have to sleep in your car and all that. And I did do that a little bit, but I could’ve just gone to my parents’ house and slept there, if I wanted to. So I was just kind of pretending to be struggling artist, just in my mind, just to entertain the idea. But it’s not so cool. There are really people who have to struggle for their art, especially now.

The Shifting Sands of the Music Industry: Adapting to Survive

Money Mark reflects on the dramatic changes in the music industry, particularly the shift to digital distribution and the devaluation of recorded music. He acknowledges the financial challenges facing contemporary musicians while also recognizing the new avenues for revenue, such as licensing and commercial partnerships. His perspective highlights the need for artists to be financially astute and adaptable in a rapidly evolving industry.

Do you think it’s easier or harder now for artists?

It depends on what it is. I think it’s still hard for a lot of people. For musicians and songwriters, the songs are free now. So we’re not making money off that. The 90s were really weird for making a shit ton of money for doing the same amount of work that people are doing now who are making no money. That doesn’t seem fair.

Owning Your Copyright: A Cornerstone of Financial Independence

One of Money Mark’s most financially savvy decisions was to retain ownership of his music copyrights. Turning down a substantial $750,000 record deal in favor of licensing agreements, he prioritized long-term financial control over immediate gains. This decision, initially questioned by his lawyer, proved prescient. Owning his catalog allowed him to benefit from licensing opportunities years later, including the extensive use of his music in Ugly Delicious. This underscores the enduring value of intellectual property and the importance of understanding copyright in the creative industries.

Early in your career, you decided you wanted to own your own catalog?

Absolutely. 1995 was my first solo record. We already had been making Beastie Boys records, so I made some money, I started a family, and I started making my own songs. I made this record called Mark’s Keyboard Repair and it did something. It did a lot, actually. And a lot of that music is actually in Ugly Delicious, twenty years later. It’s only dispersed in all those eight episodes because I own the copyright. When I was doing my record deals way back in the day, there was a ton of money being offered to me. I decided not to do it. I decided to only license my albums to these labels. I can give you a figure: $750,000 was offered to me. And I turned it down. I wanted to own my copyrights. Instead, I licensed my records to these companies and I got back maybe $125,000. My lawyer at the time was like, That’s really dumb. In 20 years, no one’s going to care about your music.

For the most part, he’s right: In twenty years, how many acts have survived? For me, it worked out, but I guess if you crunch the numbers, it wasn’t supposed to work out.

So, now I own all of my songs. I never really was corporate. Even with the Beastie Boys, technically, I was on the side.

Remaining Independent: The Power of Self-Determination

Money Mark’s choice to remain an independent artist, even during his time with the Beastie Boys, reflects a commitment to self-determination and control over his creative output and financial trajectory. He was a “hired gun” by choice, maintaining autonomy rather than becoming fully integrated into the Beastie Boys’ corporate structure. This independent stance has allowed him to navigate the music industry on his own terms and build a sustainable career across multiple decades.

What do you mean, on the side?

I was not part of a Beastie Boys company. I was only a hired gun, and I wanted it that way. I still am; I have been an independent artist this whole time. You were asking me how bands now succeed: They’re all hoping to get corporate spot, a TV commercial. That’s how their careers get kicked off.

The Apple Deal: Serendipity and Fair Compensation

The story of Money Mark’s Apple commercial and the use of his song “Push the Button” is a fascinating case study in unexpected financial windfalls and the importance of advocating for fair compensation. Initially used without permission, the situation turned into a lucrative deal, highlighting the potential, and sometimes unpredictable, financial opportunities that can arise in the digital age. His negotiation, asking for a fair $250,000, resulted in triple damages due to the unauthorized use, ultimately netting him $750,000. This anecdote underscores the importance of understanding your rights and seeking appropriate remuneration for your creative work.

Which is funny, because you were in a very early Apple commercial.

Yeah. I was the first modern solo artist to be in iTunes — the very first iTunes. A friend in San Francisco called me on my landline and told me he was watching Steve Jobs in Tokyo unveiling this iMac computer.

It was one of Apple’s Macworld events?

Yeah. Steve walks onto the stage. He said, I need some music, and he played my song, “Push the Button.” And that streamed worldwide. He didn’t ask permission or anything. Because of that, my publishers contacted them and said, “Hey, you used our client’s song.”

Steve Jobs called me, and I talked to him for like five seconds, not very long. He apologized, said, Hey I’m sorry for using your song, but it was amazing, and I think our business guys are going to work it out. I’m a fan.

And I was, Cool, and I’m a fan, too.

He said he’d use it for one year, on TV ads, and it’s also going to be on this iTunes thing. I asked for something fair at the time. I asked for $250,000. And then something weird happened: Because he didn’t ask permission ahead of time, it turned into triple damages. So I got $750,000.

That number again, $750,000.

That’s my number.

The Digital Revolution and the Future of Authorship

Money Mark’s reflections on the digital revolution extend to the concept of authorship in music and software. He contrasts the intensely collaborative nature of modern digital creations with his own more solitary, hands-on approach to music making. This observation raises important questions about the changing economics of creative work in the digital age and the value of individual artistic vision in a world of mass collaboration. His preference for a more direct connection to his tools and a smaller circle of collaborators reflects a desire for artistic and financial control in an increasingly complex landscape.

Did you have any idea about what the impact of iTunes would be, or what it would mean for music in general?

No. Nobody knew. Nobody knew. It was really weird. In the commercial, it was, You can rip it, you can burn it. And then you see it’s iTunes on an iMac and think, Yeah, if I’m going to be able to get a song and just copy it on my own, that’s kinda cool. Make my own CD!

It would burn CD one at a time. You can’t start a record label like that. But it was cool, you could share [the CD] with people.

Nobody knew. I don’t know he knew of it, either.

And now so much of music is digital.

You look on Beyonce records, or modern records, and there’s 8 or 9 or 10 contributors to this one song, and same with a movie. So it’s more like making a movie than my time. My records? I’m the only songwriter on my records. I’m the only one singing, and I’m playing 90 percent of all the instruments. So it’s just by myself, like painting or something.

It goes back to the Walter Benjamin thing, authorship. Something digital, there’s thousands of names, just to get things to turn. If you go to your computer and you go to About This Computer, it’s 10,000 names. About This Software, another 10,000 names. You’re collaborating with thousands and thousands of people. That’s how I look at it. The authorship of all the stuff that I use is much smaller, and that’s kind of how I feel more comfortable. There’s the person who made this guitar; on a tape machine, there’s a motor and a magnetic head and then the tape itself. There are a handful of authors for that. I’m working with very few people. I feel like I’m still in my bedroom, making stuff with soldering iron.

Conclusion: The Financial Keys to a Harmonious Career

Money Mark’s career is a compelling example of how creative talent, when combined with financial acumen and strategic decision-making, can lead to lasting success in the unpredictable music industry. His story offers several key takeaways for artists and creative professionals:

- Diversify Your Skills: Like Money Mark’s carpentry background, having multiple skills provides financial stability and opens up diverse income opportunities.

- Value Intellectual Property: Owning your copyrights is crucial for long-term financial security and leveraging your creative work.

- Embrace Collaboration but Protect Your Interests: Collaboration can be enriching, but understanding your value and negotiating fair terms is essential.

- Adapt to Industry Changes: The music industry is constantly evolving. Adaptability and a willingness to explore new revenue streams are vital for survival.

- Seek Mentorship and Continuous Learning: Learning from experienced professionals and embracing lifelong learning can enhance both your creative and financial skills.

Money Mark’s journey is more than just a musical success story; it’s a blueprint for building a sustainable and financially sound career in the creative field. By prioritizing independence, protecting his rights, and continually innovating, Money Mark has orchestrated a career that resonates both artistically and financially.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.