I am a product of the transformative Great Migration. As a first-generation Angeleno, with a nod to Kendrick Lamar, my family’s roots took hold in Southern California in the 1950s. My grandmother, Bernice (or Christine – the mystery of her true name and birthday remains a family anecdote for another time) Taylor, embarked on her own migration from Star, MS. She carried her children away from the confines of rural Mississippi, seeking refuge from a confluence of adversities. She sought escape from a past marked by an abusive marriage, limited opportunities, and a society that stifled her potential solely because she was a Black, dark-skinned woman. Underlying these hardships was the pervasive racism woven into the very fabric of the only nation she had ever known.

My grandmother, like countless others, unknowingly became part of the Great Migration, planting seeds that would blossom and extend across five generations under the Los Angeles sun, often veiled by smog. This movement, later termed “The Great Migration,” involved the relocation of six million Black Americans, primarily descendants of enslaved Africans. They journeyed north, east, and west, driven by the pursuit of improved economic prospects and educational advancement, while simultaneously fleeing racial violence and the oppressive grip of the Jim Crow South.

Ida Mae Brandon Gladney in 1977

Ida Mae Brandon Gladney in 1977

Confined by the rigid, often unspoken rules of the Jim Crow South, most Black individuals had only known this region. Despite legal emancipation, true freedom remained elusive. Opportunities for advancement were systematically denied. Many were relegated to the exploitative system of sharecropping, a form of tenant farming where Black families were forced to pay rent with their crop yield. This often consumed their entire annual harvest, leaving them perpetually trapped in poverty. Beyond economic hardship, they lived under the constant threat of violence. In the Jim Crow South, any perceived slight towards a white person could have fatal consequences.

Driven by the yearning for a better life, Black Southerners sought escape. For many, this path led northward, eastward, and westward. Those who successfully navigated this exodus paved the way for their families. In the 1910s, the Great Migration began to take shape. Initially a trickle, the movement gained momentum as migrants shared accounts of their improved lives in new lands, igniting hope in those still enduring hardship in the South.

The Great Migration undoubtedly unlocked opportunities, yet the promised land was not without its own forms of oppression, albeit different in nature. Isabel Wilkerson’s seminal work, The Warmth of Other Suns, masterfully chronicles the journeys of three individuals who carried their aspirations and families from distinct corners of the South to diverse destinations across the nation during various phases of the sixty-year Great Migration.

One such narrative is that of Ida Mae Brandon Gladney. Born and raised in rural Mississippi, Ida Mae and her husband George were cotton sharecroppers. For years, they toiled to merely “break even” under a landowner considered relatively fair for the time. In 1937, Ida Mae and George decided to flee Mississippi with their two young children. This drastic decision was spurred by a violent incident where a family member was nearly beaten to death over missing turkeys belonging to a white man. They packed their meager belongings and secretly left Mississippi.

Ida Mae recounted her experiences in Chicago through interviews with Wilkerson. While Chicago offered freedom from the overt racism of Jim Crow Mississippi, it presented a new set of challenges. These included housing segregation, unemployment, the scourge of drugs and violence, and the pressure to assimilate into a new culture. Migrants felt compelled to emulate Black individuals who had resided in the North for longer, those who had shed their Southern identities. Ida Mae described her struggle to reconcile her identity with the expectations of Chicago, and the challenge of instilling her Southern values in her children, who were being raised in a vastly different environment with a different set of rules.

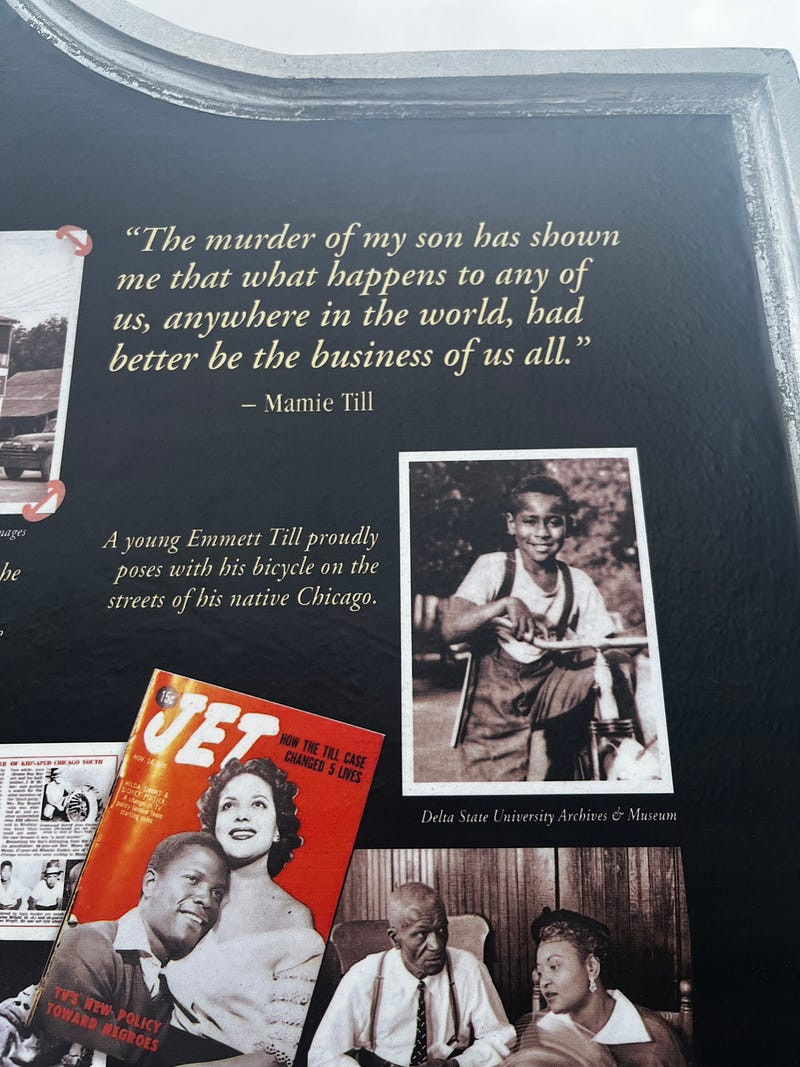

This internal conflict resurfaced when Ida Mae attended the funeral of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old lynching victim. Till, like many first-generation Northerners, had only heard stories of the South and its ways. He, like myself, was a product of the Great Migration, his lineage rooted in rural Mississippi. Emmett Till had grown up with freedoms unknown to previous generations, including his mother. While undoubtedly aware of the struggles faced by young Black boys in Chicago, it’s likely he never had to suppress his gaze or step off a sidewalk out of fear of violent reprisal from white individuals. His ancestry was intertwined with the land of rural Mississippi, but he was fortunate to be distanced from the horrors his predecessors had endured.

My own encounter with a fragment of Till’s reality occurred during a visit to rural Mississippi, specifically Greenwood. Once the epicenter of cotton planter society and hailed as the cotton capital of the world, Greenwood lies on the eastern edge of the Mississippi Delta. Its development stemmed from the confluence of the Tallahatchie and Yalobusha rivers, which converge to form the Yazoo River.

Bryant’s Grocery in Money, Mississippi

Bryant’s Grocery in Money, Mississippi

Greenwood is conveniently located a mere two-hour drive south of Memphis. Upon arriving, it becomes evident that unless you have roots or connections there, there is little reason to visit. In Greenwood, a sense of old-fashioned Southern hospitality persists. People still greet strangers in convenience stores and wave as they pass. Men address familiar women as “gul,” hold doors open, and uphold the tradition of “ladies first.” Black women in Greenwood, who might be assertive leaders elsewhere, adopt a quieter demeanor in the presence of men, their domain seemingly confined to the home, yet they wield considerable influence, subtly guiding their families in a manner reminiscent of their matriarchal forebears.

In Greenwood, newcomers are often met with inquiries from locals, seeking to place them within the community. Questions like “Who’s yo Mama?” are common, and context is sought from trusted acquaintances with queries like “Whose daughter is this?” Greenwood evokes the kind of town one knows exists only through family stories or perhaps an independent film. Roads outnumber streets, trees abound, the Delta stretches deep, and mosquitos are so pervasive they are jokingly referred to as “dragons” who consider insect repellent a mere fragrance and occupy so much space they might as well be charged rent.

Intriguingly, Greenwood, once the cotton capital, built on the backs of enslaved people, now holds another somber distinction. In its largely deserted downtown stands the solitary statue of Emmett Till. Barely protected by a flimsy gate and partially shrouded in a tarp and duct tape – a feeble attempt to mitigate further damage from what appears to be a sledgehammer attack – the statue commemorates the young boy abducted, tortured, and murdered just twelve miles away in Money, MS.

Money, Mississippi, a name now inextricably linked with tragedy, claimed young Till’s life in the summer of 1955. It is often said that Till’s unfamiliarity with the customs of the old South contributed to his demise. However, the true culprit was unequivocally racism. No individual should ever bear the responsibility of diminishing themselves to appease another’s prejudice. Regardless, Till, despite warnings, was unaware of the unwritten rules of the Jim Crow South and had never experienced its brutal realities.

Sign marking the historic site of Bryant’s Grocery

Sign marking the historic site of Bryant’s Grocery

In 2024, the world has undergone modernization and a technological revolution, shrinking distances and granting access to vast amounts of information. Yet, even now, the Deep South retains echoes of its past. Similar to Till, who reportedly received a cautionary lecture from his mother before his trip from Chicago to Money, I was advised on how to behave in Greenwood, particularly “across the tracks.” My ignorance of the enduring customs of the Deep South became apparent during a visit to Greenwood’s Market Place store. On my way to the checkout, I encountered a display featuring thin blue line merchandise and pro-2nd amendment apparel. The overtness of these items in the city’s marketplace was jarring. I was quickly ushered away by a friend, a Greenwood native who, unlike Till or myself, understood the unspoken codes. As I paused, contemplating the display, I was told to “come on,” with the implicit understanding, “you already know what it is.”

It dawned on me then that even those who had left Greenwood carried its ways within them, reverting to them upon return for survival. For them, accepting things as they were was ingrained, a matter of self-preservation. As a Californian, while aware of differing social norms in “middle” America, I had never truly grasped the extent to which one had to “mind their manners” in the way that natives of rural Mississippi and the Deep South simply knew as a way of life. My innocent questioning of the status quo was perceived as a dangerous probing of unwritten rules that still held sway over the hearts and minds of people in the Deep South, a stark reminder of the enduring legacy of places like Money, MS, and the long shadow of the Jim Crow era.