The age-old debate of “old money” versus “new money” has always been a fascinating lens through which society examines wealth and status. Historically, the source of wealth dictated social standing just as much as the amount. Nowhere was this dynamic more dramatically illustrated than in the opera house saga of old New York City, a battleground where the burgeoning “new money” class definitively asserted its power over the established “old money” elite.

If you are acquainted with the works of Edith Wharton, the celebrated chronicler of New York’s high society, the Academy of Music will likely ring a bell. This venue, the heart of the city’s opera scene for decades, is vividly depicted in the opening scene of The Age of Innocence. Wharton sets the stage:

On a January evening of the early seventies, Christine Nilsson was singing in Faust at the Academy of Music in New York. Though there was already talk of the erection, in remote metropolitan distances ‘above the Forties’. of a new Opera House which should compete in costliness and splendor with those the great European capitals, the world of fashion was still content to reassemble every winter in the shabby red and gold boxes of the sociable Old Academy. Conservatives cherished it for being small and inconvenient, thus keeping out the ‘new people’ whom New York was beginning to dread and yet be drawn to…

This passage perfectly captures the societal friction between old and new wealth, showcasing how the newly rich, unable to penetrate the old guard’s circles, chose to forge their own path. But before delving into the rise of their opulent alternative “above the Forties,” let’s explore the significance of the Academy of Music, a quintessential “Old Money House” of its time.

Elegant woman in vintage attire, embodying old money aesthetics and the timeless style of established wealth.

Elegant woman in vintage attire, embodying old money aesthetics and the timeless style of established wealth.

The Academy of Music was more than just an opera venue; it was a versatile space that hosted everything from operas and concerts to public meetings and political rallies. When it first opened its doors, The New York Times in 1854 lauded its modern features, such as “spring seats so that they fold up when not in use.” However, the praise was not unqualified. The horseshoe-shaped layout, while perhaps fostering a sense of intimacy, was criticized for obstructing views. As The Times wryly noted, “a giraffe could not see round some of the corners.”

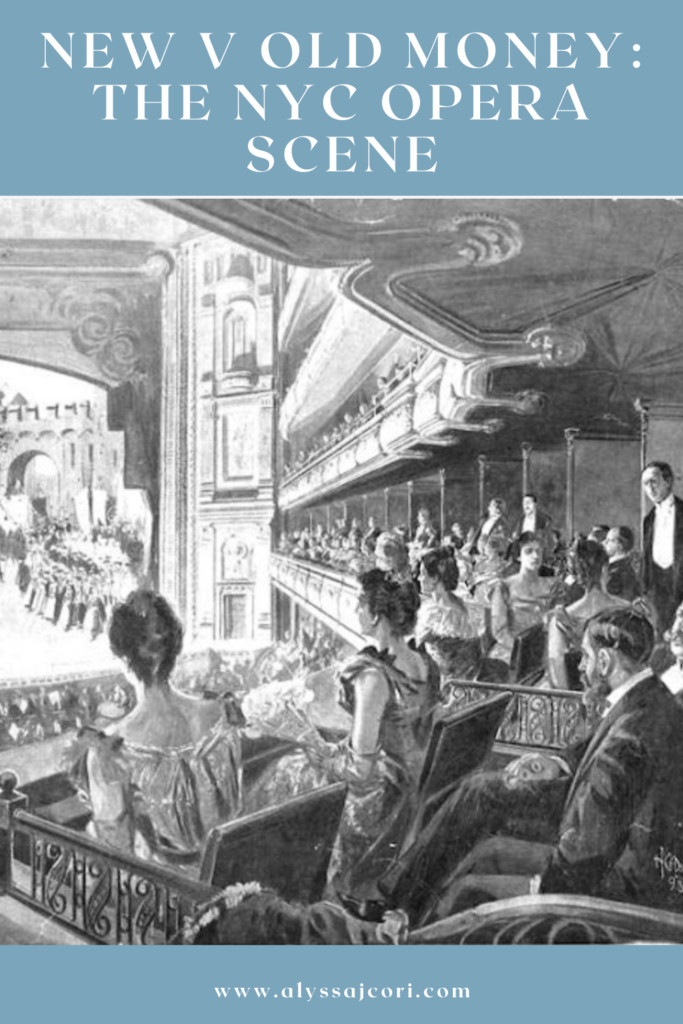

The newspaper concluded that “in an acoustical point of view, the New Academy of Music is a triumph…in every other aspect the Academy is a decided failure.” Essentially, while the acoustics were excellent, the viewing experience was often compromised. However, for the patrons of the Academy, attending was less about seeing the performance and more about being seen at the performance. As Wharton’s Age of Innocence illustrates, the social dynamics within the audience, the subtle cues of status displayed in box seating, and adherence to social “form” were the real spectacles.

The Academy of Music, New York City's original opera house and a symbol of old money society in the late 19th century.

The Academy of Music, New York City's original opera house and a symbol of old money society in the late 19th century.

So, what spurred the “new money” set to establish their own opera house? Was it a sudden surge in artistic appreciation, a desire for unobstructed views of the stage? The reality was more about social space than stage space. The Academy of Music, with its finite number of boxes, was effectively a closed club. Families like the Morgans, Rockefellers, and Vanderbilts, representing the burgeoning industrial fortunes of the era, found themselves unable to secure a box – the ultimate symbol of social arrival within the “old money house.”

The snub was not taken lightly. These newly wealthy families, accustomed to wielding influence in business and industry, decided to leverage their financial might to create their own institution. When they formally incorporated to fund a new opera house, the Academy of Music, in a belated and somewhat comical attempt to retain its dominance, announced the addition of twenty-six new boxes. But the gesture was too little, too late. The “new money” families, having felt the sting of exclusion, were no longer interested in joining the “old money house”—they were building their own mansion.

This marked the birth of the Metropolitan Opera House.

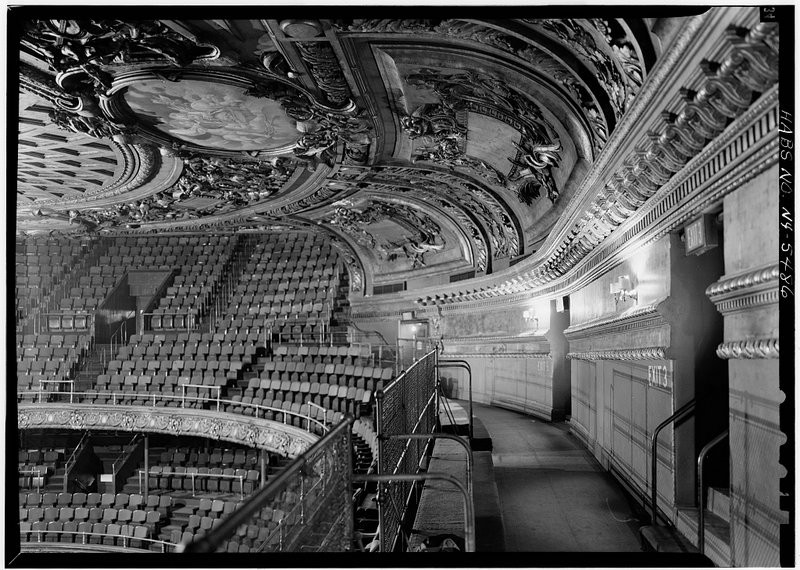

The original Metropolitan Opera House on 39th Street, a grand 'new money house' built to rival the Academy of Music in New York City.

The original Metropolitan Opera House on 39th Street, a grand 'new money house' built to rival the Academy of Music in New York City.

The Metropolitan Opera House opened its doors in 1883 on 39th Street, slightly south of the initially predicted “above the Forties” location. From its inception, the Met was designed to outshine the Academy in grandeur and prestige, a clear declaration that “new money” had arrived and was ready to set its own standards. Except for a season of restoration following a fire in 1892-93, the Met flourished, quickly eclipsing the Academy of Music as the city’s premier opera house. This was more than just a change of venue; it was a symbolic coup. The “new snobs,” as the article playfully puts it, had indeed arrived, establishing their own “new money house” and redefining New York’s social and cultural landscape.

Over time, the Metropolitan Opera House adapted to changing societal norms. By 1940, the original wealthy families were no longer the sole proprietors. A non-profit organization was established to manage the opera house, reflecting a shift towards broader public access and evolving philanthropic models. The grand tier’s private boxes, once the exclusive domains of the elite, were converted into standard seating, further democratizing the space. In 1966, the Met moved to Lincoln Center, embarking on another chapter in its storied history, leaving the original “new money house” on 39th Street behind, but cementing its legacy as a cultural institution born from the dynamic interplay between old and new wealth in New York City.